Tanzania’s 2020 Elections amid of COVID-19 Pandemic – to Happen or Not?

Dr. Victoria Lihiru

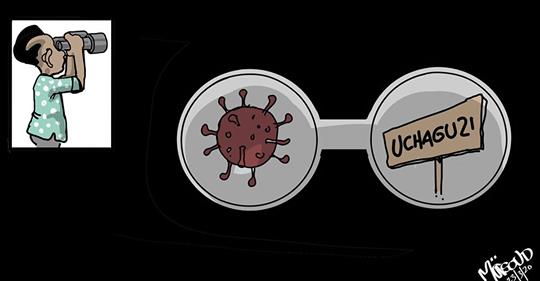

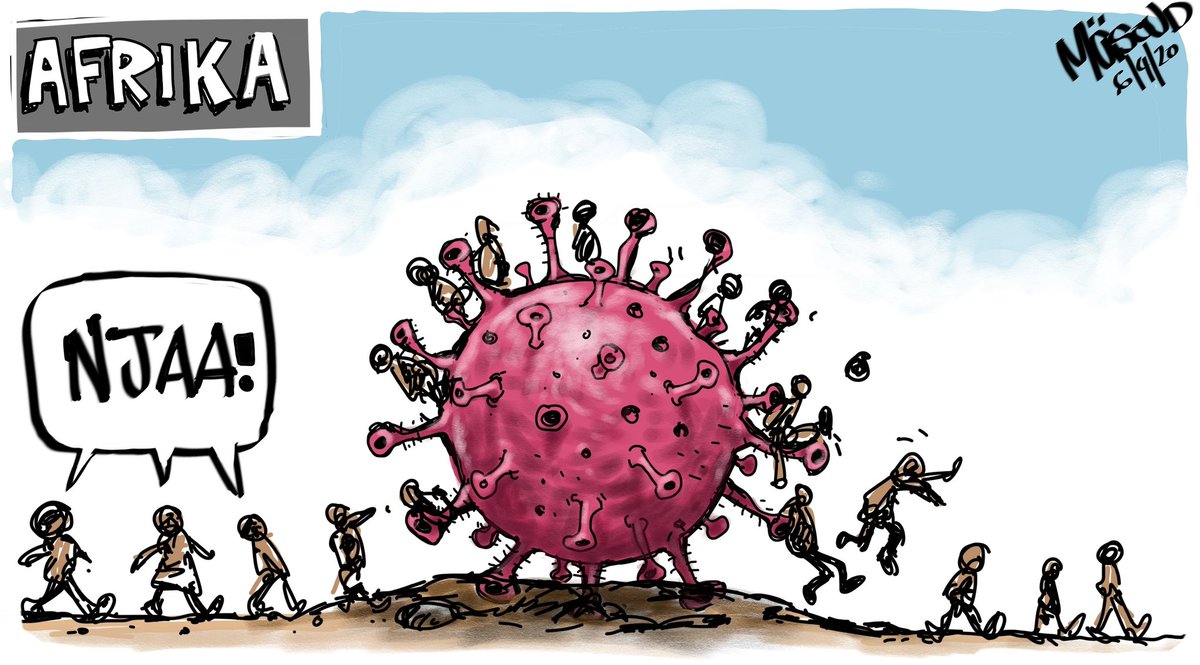

Without Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the picture, the year 2020 would have witnessed 12 African countries conduct general elections. These include presidential, legislative and/or local elections. Such cyclic elections allow citizens to reconfirm or replace elected representatives. However, with more than 10,000 COVID-19 reported cases in Africa, it is clear that the pandemic is not just a health issue. It is also a key consideration in conducting the planned elections in the continent.

Electoral activities, by nature, encourage mass participation. They are thus counterproductive to the physical distancing measures to curb further spread of coronavirus. Under the circumstances where the world is grappling to manage the social-economic impact of the pandemic, elections can be considered a distraction to the country’s efforts to battle the disease. There is a reasonable expectation that sufficient attention, energy, and resources need to be directed towards combatting the deadly virus. Owing to its fast spread , by early April 2020 at least seven countries had postponed envisaged national and subnational elections and by-elections. These are: Kenya, Nigeria, Tunisia, Zimbabwe, Gambia, Ethiopia, and South Africa.

In Tanzania, the year 2020 started with high hopes regarding the nature of elections the country is going to have. Despite endless and unattended demands for an independent electoral commission and the need for rectification of the flaws in the electoral legal framework, President John Magufuli assured electoral stakeholders that the October 2020 elections will be free and fair. Hesitant to share a complete strategy, the President hastened to restore the confidence of stakeholders by assuring that the internal and external electoral observers and monitors would be allowed.

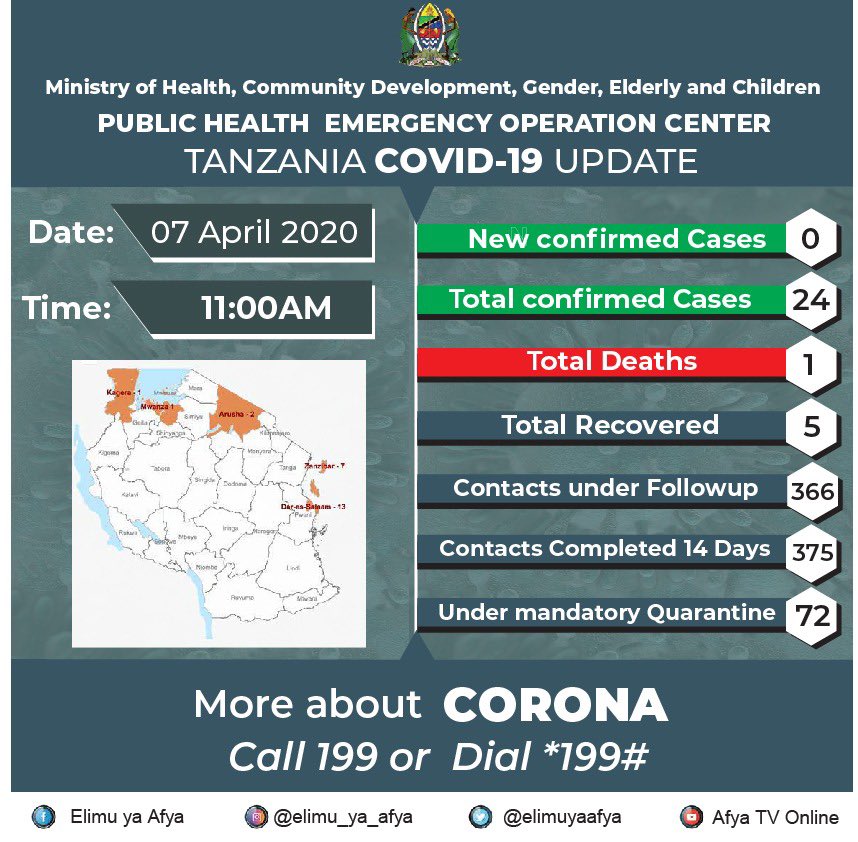

COVID-19 brings new dynamics, calling for reconsideration on whether to hold the planned polls or to postpone them. Even though Tanzania’s elections are scheduled to take place in October 2020, scientists warn the world that physical distancing measures may need to be observed for several months for successful containment of the virus. Tanzania has, to a large extent, succeeded in its hand washing campaign and claims to have maintained its COVID-19 spread to twenty four cases only. With the COVID-19 coordination committee-under the leadership of the Prime Minister, it is believed that the country is in the process of preparing a-currently-high-time needed comprehensive and inclusive COVID-19 response plan. However, it remains unclear whether Tanzania will change its stance on ruling out the possibility of a total lockdown and mass testing.

Astonishingly, although Tanzania is a secular state and the fact that public religious activities have caused widespread of the COVID-19 virus in South Korea, Malaysia and other places, they are not banned with a view that people need God the most in these trying times. The irony is, some political leaders are gathering people in a manner that abuse the physical distancing precautions to teach them about physical distancing. This state of affairs hikes the probability of the country to experience a full-blown COVID-19 pandemic.

Amid the country’s reportage of its 13th coronavirus case, President Magufuli gave further assurance that COVID-19 is not close to affecting the electoral plans. Attempts to postpone elections always attract public concerns on potential abuse, particularly under a presumption that the incumbent government may want to undemocratically stay in power. Hence, the decision to carry on with the election is somewhat commendable. One concern is that, despite the sensitivity attached to elections, there is no evidence whether the President’s decision, to carry on with elections, was informed by consultations with key electoral stakeholders.

The credibility of electoral process is measured by the effectiveness in the execution of its technical aspects, coupled with abroad, genuine and meaningful participation of key stakeholders. Although the President has made an announcement, it is critical for his decision to be evidence-based and inclusive, hence it should be revisited. The National Electoral Commission (NEC) of Tanzania, the Zanzibar Electoral Commission (ZEC) and the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP) should leverage technological platforms and hold consultative meetings with electoral stakeholders to reflect on the implications of COVID-19 on the planned elections.Then they should jointly make a decision on whether to hold or postpone the October general elections. It is important to recall that postponement of elections in Tanzania is precedented, but it was a brief one.

Careful consideration should, therefore, be on the following questions;

a. How will the internal party nominations; voter’ education; and electoral capacity building trainings to actors and poll workers be conducted amidst COVID-19?

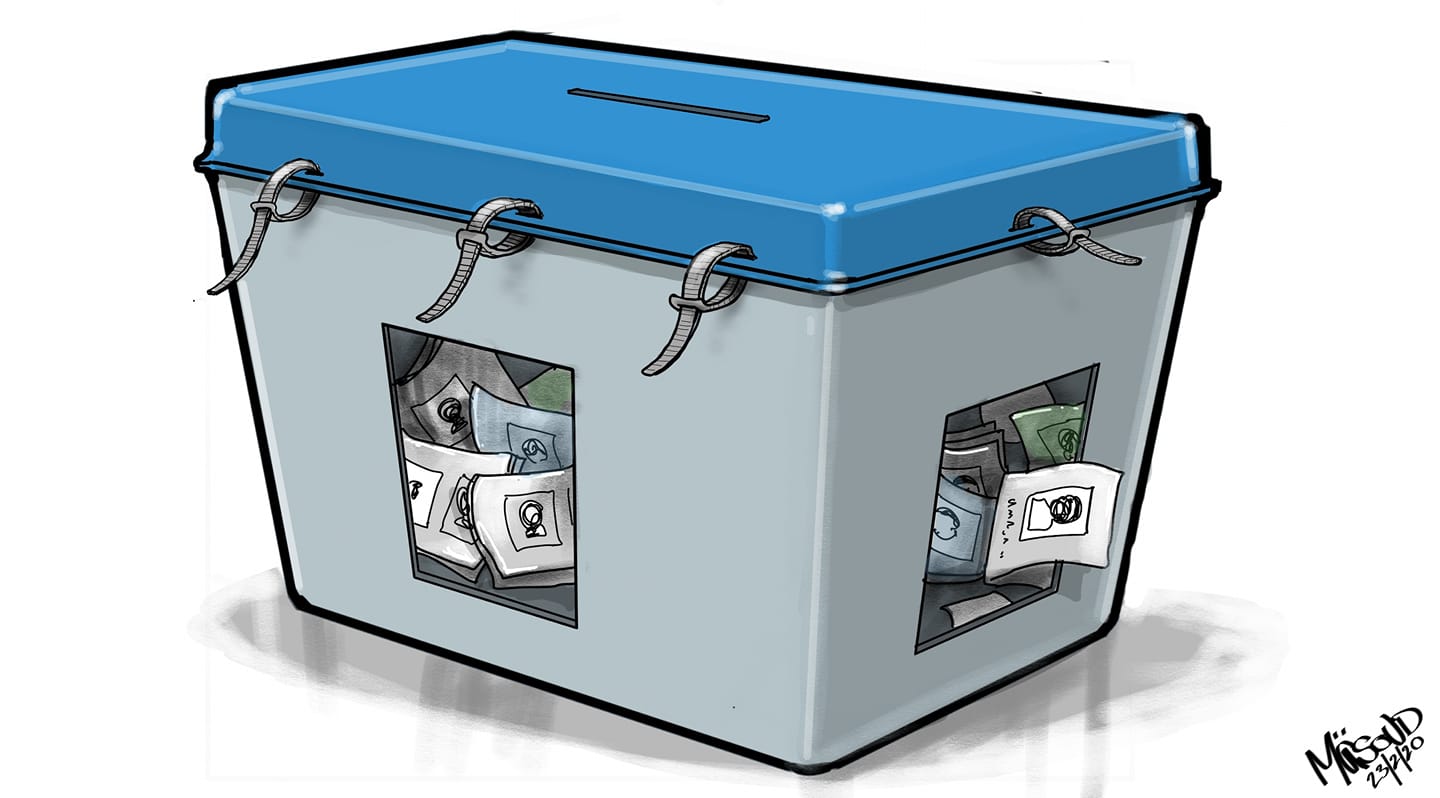

b. What would be the complications involved in the production and distribution of ballot papers, voting booths, seals and other supplies needed during elections and possible navigation strategies?

c. How will electoral campaigns, polling stations voting, and counting adapt to physical distancing measures while ensuring credibility of the process and results?

d. What implications would the possibility of low voter turnout have on the overall election legitimacy, caused by a genuine fear to come out for voting by older people, people with disabilities and those with underlying medical conditions?

e. The effectiveness of any technology that may be deployed to complement polling-station-based voting i.e. postal, internet, and mobile in terms of inclusivity, user-friendliness, affordability, and accessibility by all people, and accuracy of results.

The additional cost and time for the technological and logistical adjustments needed to deliver the elections amid COVID-19 should be based on cost-benefit analyses. In this regard, the dire need to tighten the country’s measures to curb further spread of the virus, cushion its impact on the economy, and the people should be compared with the implications of postponing elections and conducting them in the near future. In case the decision is postponement, clear pathways to guide institutions, actors, and stakeholders’ conduct during the extension period, and timelines for next elections must be agreed upon i.e. as a consensus.

On procedures for election postponement, the Constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania, 1977 as amended from time time, which was to provide guidance on how to treat elections during the unforeseen events such as COVID-19, reminds us how desperately Tanzania needs a new Constitution. Article 42(4) of the Constitution allows the Parliament of Tanzania to pass a resolution to postpone an election for a period not exceeding six months, if the country is at war and the President thinks that it is not possible to hold elections. Also, when the United Republic is at war, Article 90 (3) of the same Constitution allows the life of the Parliament to be extended for a period not exceeding twelve months each time provided that such extension will not exceed a period of five years.

While the day-by-day ever-developing advice of epidemiologists and public health officials presuppose that electoral activities would be counterproductive to the prescribed mitigation measures to counter the virus, the Grundnorm suffers tardiness and consequently fails to provide the needed guidance in these critical times. To allow suspension of October elections and extension of parliamentary life beyond its five years, which is about to be completed, Article 98 of the Constitution needs to be invoked. A Bill to provide for postponement of elections and extension of parliamentary life due to unforeseen events or pandemics needs to be introduced and supported by not less than two-thirds of all parliamentarians.

Given the existence of certificate of urgency procedure and the seriousness of the COVID-19 pandemic, such amendment is feasible. The only worry is whether in the same circumstances key stakeholders’ will be genuinely involved to shape the content of the Bill. The current practice by the Legal and Constitutional Parliamentary Committee, however, exposes its stakeholders’ engagement strategy as incompatible to parameters for conducting participatory legislative processes.

—

Victoria Lihiru is Lecturer of Law at the Open University of Tanzania. She is also a Governance, Gender and Disability Inclusion Advisor. Reach the author via email: victorialihiru@gmail.com