A decades-long debate has resurfaced. It concerns the likely move to resettle resident Maasai pastoralists from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) in Tanzania. The main explanation provided is the threat they allegedly pose to the sustainability of ecology and wildlife tourism.

On the contrary, the Maasai claim ancestral rights to the land and that their livelihood system (livestock husbandry) is compatible with wildlife and the environment. Besides, the law that saw the birth of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA) provides for the Maasai legal occupation. It is on the backdrop of this context that I argue that the Multiple Land-Use Model (MLUM) buttressing the area’s management for over half a century is a conservation scam and was destined to fail right from the outset.

In the beginning

According to NCA’s first Conservator, Henry A. Fosbrooke, the habitation of NCA can be traced to about 2300 years ago with the existence of pastoralists named “Stone Bowl People.” They were christened so from their use of stones for shelters and cattle pens. These pastoralists were traced in the Serengeti plains.

The first dwellers in the Ngorongoro crater, some 300 years ago, are the Tatoga. They are also a pastoral society. Up until recently, they were visiting their ancestors’ grave cairns and sacred trees in the crater.

The Maasai came to the area 100 years later and established their early settlements around the Natron-Manyara area, which the Tatoga were already occupying. A territorial struggle ensued and the Maasai expanded to the crater. It is believed the Maasai entered the crater through a cattle track that had existed before their arrival. The track is evidence of the Tatoga occupation in the crater before Maasai’s arrival. However, it is the Maasai settlement in the area that is more authenticated with evidence from 19th-century trade caravans pointing to them.

In 1890 two concurrent calamities occurred that drastically decimated both human and livestock populations: smallpox and rinderpest. It is believed the calamities were so catastrophic that a German settler by the name of Siedentopf claimed and settled in the crater unopposed. However, other sources indicate that the settler and his brother “fought the Maasai.” These settlers went on to build a herd of 1500 cattle only to be stopped in 1916 by his superiors due to the war situation.

Following Britain’s victory in the war, the property fell in the hands of a British settler in the 1920s, Sir Charles Ross. He only utilized a third of the property as a hunting lodge making no substantial developments. In 1935 the government revoked Ross’ lease on grounds of non-development.

In the late 1920s, some government workers were also posted to stay on the property. These were engaged in farming activities under the government’s watch. Substantial cultivation ensued on the South of Lerai forest. Illegal farms were also established by locals in the Laitokitok and Engare Rongai areas. But the days of farming in the crater were numbered, wildlife conservation was just around the corner.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area is born

Conservation efforts in the NCA started with the establishment of Serengeti National Park in 1940. At that time, the Ngorongoro highland area (except Endulen-Kakesio) was part of the new park. According to Fosbrooke, the 10,000 Maasai and a handful of Waarusha living in the area were assured that they were protected by law. On different occasions, the Maasai District Commissioner in 1952 and the Governor himself in 1954 affirmed that the position of the government is safeguarding the welfare of resident Maasai in the park. Speaking to the elders of Ngorongoro, the Governor stressed that:

I wish at once to reassure you that all Maasai and other pastoralists who have been normally resident within the area of the park will not be turned out.

In 1958 things took a radical turn when the Maasai agreed to surrender the whole of western Serengeti in exchange with the Ngorongoro highland and the crater. The following year NCA came into being under the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Ordinance No. 14 of 1959. Even then, the government stressed it would safeguard Maasai’s welfare, albeit with some conditionality. While giving a speech to the Maasai Council on 27 August 1959, the governor stated:

It is the intention of the government to develop the crater in the interest of those who use it…but should there be any conflict between the interest of the game and the human inhabitants, those of the latter must take precedence.

Although allowed to stay, the Maasai were to adhere dully to the wildlife laws which they did ostensibly except for rhino poaching that was linked to Maasai spearing. Fosbrooke, however, emphasized that rhino poaching was largely due to laxity and/or active involvement of the non-Maasai (NCAA) staff. He argued that the sophistication used in killing rhinos, including cutting out and removing bullets, to avoid tracing suggested the involvement of more educated and sophisticated people from outside.

Then came April 1974 when a series of events in the Ngorongoro took yet another turn in the name of wildlife conservation, this time with dire repercussions. The resident Maasai were ruthlessly expelled from the crater. Fosbrooke’s estimates indicate that three resident Bomas, 150 human inhabitants, around 1500 cattle, and 1000 small stocks were all made to disappear even without a few-days prior notice. He writes that as of 1989, it was clear that the authority had failed in fulfilling its legal obligation of protecting the rights of resident Maasai given the 1975 amendment of the Conservation Area Ordinance of 1959. This was the reason for his recommendation to abolish the NCAA and reinstate the Unit that managed NCA between 1963 and 1975.

Therefore, the NCAA had been founded on the embracement of the rights of resident Maasai and their protection. This foundation was paramount even at the cost of other functions, in this case wildlife conservation and tourism. Given that, it became apparent that the post-independence government had no true intention of upholding the MLUM in the area and especially the rights of resident Maasai.

Trumping on the Maasai rights

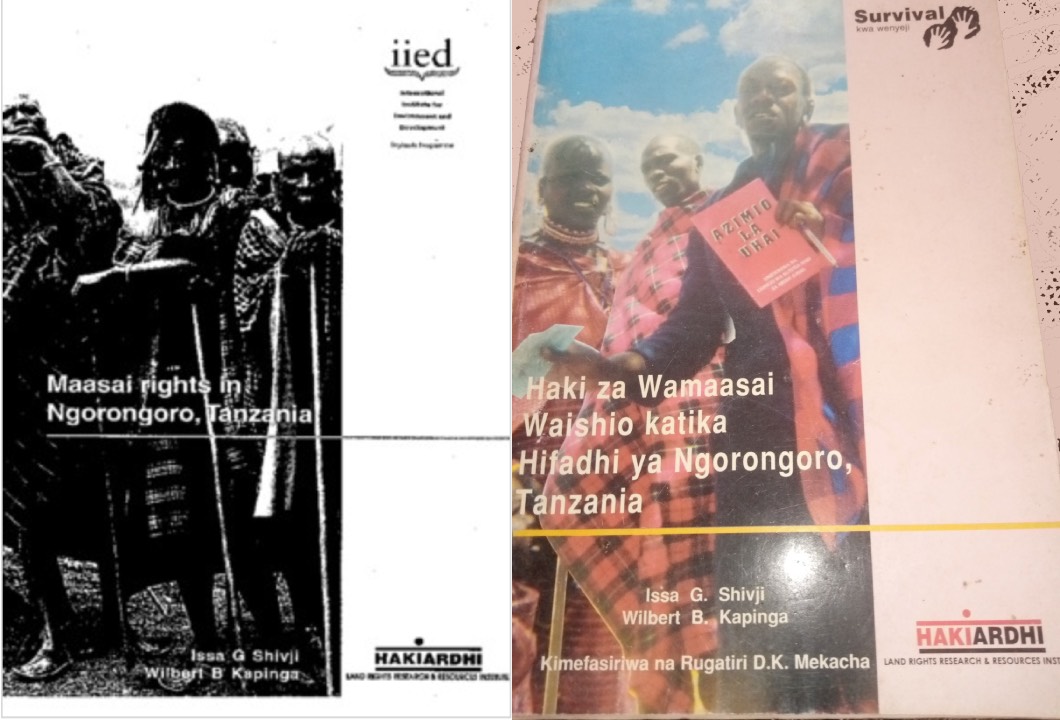

In their compelling account on the Maasai rights in Ngorongoro, Issa G. Shivji and Wilbert B. Kapinga point out three bundles of rights that they deem extremely restrained among the Maasai in the NCA. These are the right to life and livelihood; the right to freedom of association, assembly, and expression; and the right to participation, consultation, and representation. For this piece, I will focus on the thorny question of the right to life and livelihood.

Systemic repression of a range of civil rights is one of the distinguishing features of post-independence Tanzania. The NCA is unique in that resident Maasai there face yet an additional arm of state repression through the NCAA. Since the Authority’s inception in 1959, rights of grazing access, salt licks in the crater, and cultivation have been seriously restricted.

Systemic repression of a range of civil rights is one of the distinguishing features of post-independence Tanzania. The NCA is unique in that resident Maasai there face yet an additional arm of state repression through the NCAA. Since the Authority’s inception in 1959, rights of grazing access, salt licks in the crater, and cultivation have been seriously restricted.

This is evidenced by the total banning of cultivation and eviction of Maasai from the crater floor following the 1975 amendment. The ban and eviction were due to concerns about wildlife and ecosystem degradation. A ban on cultivation has always resulted in serious welfare impacts such as hunger and malnutrition among resident Maasai. Ironically, the systemic impoverishment of the resident Maasai was called out even in the 1989 International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) report which blamed the NCAA for unclear management policy and poor commitment to the development of the local community.

At the request of the NCA Conservator, Randall B. Boone and fellow researchers embarked on a study in the early 2000s to assess the impact of cultivation on livestock, wildlife, and people. But they found no significant change in the wildlife population with the presence of cultivation or otherwise in the NCA. They concluded that devoting about 1% or lesser of the NCA to cultivation is necessary for Maasai wellbeing and would not harm livestock or wildlife population. So, the persistent opposition towards cultivation by NCAA could only be justified by the notion that it detracts from tourists’ interests.

The cultivation question aside, the blame has now shifted to an unbearable number (population) of the Maasai in the area, which is now around 100,000 from about 8000 Maasai in 1959. The protagonists of the population narrative claim that the population is likely to push the NCA’s wildlife and environment to extinction unless the Maasai are evicted. Condemning the Maasai in NCA for growing in numbers, especially if that happens naturally through reproduction is a gross violation of their rights. If the increase has resulted from emigration to the NCA, it is puzzling why the resident Maasai should be blamed and not the NCAA. The latter enjoys legal powers to restrict entry into the area for people who are not residents and/or have no business in the NCA.

The cultivation question aside, the blame has now shifted to an unbearable number (population) of the Maasai in the area, which is now around 100,000 from about 8000 Maasai in 1959. The protagonists of the population narrative claim that the population is likely to push the NCA’s wildlife and environment to extinction unless the Maasai are evicted. Condemning the Maasai in NCA for growing in numbers, especially if that happens naturally through reproduction is a gross violation of their rights. If the increase has resulted from emigration to the NCA, it is puzzling why the resident Maasai should be blamed and not the NCAA. The latter enjoys legal powers to restrict entry into the area for people who are not residents and/or have no business in the NCA.

In the last quarter of 1989 when the IUCN’s “Ngorongoro Conservation and Development Project” was ending, Fosbrooke expressed his concern (in an opinion piece titled “Ngorongoro at the Crossroads”) about the uncertain future of the area. At the time, he cited three critical challenges that were facing the NCA: Maasai population pressure and concomitant demand for food; demand for tourist accommodation and vehicle pressure on the environment; and more importantly, inadequate administration.

Fosbrooke thus provided 13 proposals for the development of the area going forward. He regarded the proposals too radical that he feared they would find their way to decision-makers. Notably, he emphasized the inclusion of a policy pronouncement in all (documents for future) plans that NCA is home to resident Maasai.

On the population question and its threat to NCA’s existence, Fosbrooke suggested three solutions: emigration by resident Maasai to somewhere they can cultivate and keep livestock; farming cooperatives by locals to raise food in adjacent areas; the NCAA to cultivate food on behalf of the resident population.

In my opinion, the first suggestion does not surprise me because it seems that Fosbrooke was not naïve to think that the government would always uphold the MLUM given his experience and knowledge of the NCA management, especially after the events of 1975. It is a radical proposition but one that cannot be ignored should the government stick to its plan to evacuate the Maasai from NCA as the pressure to do so now is unprecedented.

The international conservation lobby groups

Since its inception, the NCAA has entertained a very strong presence of international conservation lobby groups, notably the IUCN, the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Peter J. Rogers argues that the international conservation lobbies play a large, if not central, role in the management of the NCA. Examples are the IUCN’s late 1980s Ngorongoro Conservation and Development Project and FZS’s central support to the current form of NCAA through its Rhino Project.

These organizations are also accused of being secretive when it comes to their dealings within the NCA and in cooperation with the Authority. For example, upon UNESCO’s threat to scrap the NCA from the World Heritage Sites list on allegation of expanding cultivation among other things, a ban on cultivation was reinstated in 2009. This heightened the impoverishment of residents in the area. It is very difficult to regard the NCA as an area where resident Maasai livelihoods can thrive given such circumstances. This refutes the whole logic behind the MLUM. If anything, it is apparent that their (Maasai) welfare is not in the best interest of the NCAA and the international conservation lobby backing it.

Therefore, it did not come as a surprise when in 2019 UNESCO urged the Tanzanian authorities to ‘voluntarily’ relocate the resident Maasai through increasing ‘incentives’ for them (Maasai) to do so. This proposal seems to have been accepted by the NCAA and the Tanzanian government bringing us to the current situation in the NCA. The rekindled debate that has been raging on for about two years now has taken a fiery turn.

So, the question is, for whose benefit is Tanzania conserving its wildlife resources? If it is for all Tanzanians, then why should some pay such a huge price? Why does wildlife conservation have to override people’s livelihoods? There is one ‘logical’ explanation: rents.

Is there too much money in NCA to let go?

Apart from its international conservation and cultural heritage significance, the NCA is probably the leading forex earner in the country’s tourism sector. Conservative estimates from 2016 indicate that the NCA received 1 million visitors and earned the sum of USD 70 million (USD 70 per visitor) as entry fees only. About 0.12% of the fees go to the district authority and the rest to the central government.

So, in that year, only USD 85,000 were retained at the district. It is further estimated that each safari tourist spends between USD 200 and 400 per day, multiplying this by the 1 million visitors in 2016 gives you between USD 200 and 400 million as daily turnover accruing to the tourism industry. With only USD 70 million going to the NCAA, the rest of the money finds its way among travel agents and airlines (mostly foreign), local tour operators, accommodation facilities and personnel, and other service providers to the sector e.g., banks, retailers, etc.

So, in that year, only USD 85,000 were retained at the district. It is further estimated that each safari tourist spends between USD 200 and 400 per day, multiplying this by the 1 million visitors in 2016 gives you between USD 200 and 400 million as daily turnover accruing to the tourism industry. With only USD 70 million going to the NCAA, the rest of the money finds its way among travel agents and airlines (mostly foreign), local tour operators, accommodation facilities and personnel, and other service providers to the sector e.g., banks, retailers, etc.

These conservative estimates indicate just how much the NCA is worth in terms of tourism revenues alone. It thus provides a strong justification for the government to safeguard such a cash stream at any cost. Factoring in the money that goes to different players across the tourism value chain one may come to terms with a half-century long Maasai predicament in the NCA and why their eviction in the name of conservation and tourism seems justifiable to the powers that be. The situation portrays a very gloomy future for the resident Maasai in NCA.

What does the future hold for the Resident Maasai in NCA?

There is a tell-tale indication that this time there may not be going back for the government. In late 2020, the NCAA convened in Arusha a workshop bringing together editors and journalists from different media houses in the country as part of the NCAA’s tourism promotion campaign. It used that platform to air the Authority’s concern over the threat to NCA’s environment by the resident Maasai.

Media campaigns that ensued afterward painted the Maasai in the NCA as a threat to conservation and tourism ostensibly due to their large numbers and that of their livestock. And, if they are not evicted, Ngorongoro will become history. As research has shown, the Maasai predicament in the NCA is a long-term systemic marginalization aimed at impoverishing their living condition to render them relocatable and appropriation of their land justifiable.

Since ascending to power, President Samia Suluhu Hassan has indicated the likelihood of the Maasai being evicted from the NCA, especially if their remaining there would jeopardize conservation and tourism efforts. This has served only to escalate the fierce debate that has lasted for decades. At the time of writing the Prime Minister, Hon. Majaliwa Kassim Majaliwa had just completed an official tour in Ngorongoro and Loliondo. While there, the Premier said that government will ensure the welfare of the Maasai is safeguarded and went on to offer that those who are ready to vacate the area voluntarily will be supported by the government.

Since ascending to power, President Samia Suluhu Hassan has indicated the likelihood of the Maasai being evicted from the NCA, especially if their remaining there would jeopardize conservation and tourism efforts. This has served only to escalate the fierce debate that has lasted for decades. At the time of writing the Prime Minister, Hon. Majaliwa Kassim Majaliwa had just completed an official tour in Ngorongoro and Loliondo. While there, the Premier said that government will ensure the welfare of the Maasai is safeguarded and went on to offer that those who are ready to vacate the area voluntarily will be supported by the government.

The question then is: what will happen to those who are not ready to relocate voluntarily? Whatever the outcome this will bring, it is very likely the NCA and the lives of resident Maasai who have depended on it for over two centuries will never be the same again.

Nice piece from you as always as ever. I loved the history attached to it. Sometimes I am marveled with the generation of the 1950s to 1970s, looking at their thinking and writing of course. They were very clever, I presume! Imagine the ideas of Fosbrooke! The conclusion sasa,….what will happen? I have enjoyed reading Kaka.

The Article is really nice.

Credible paper ever.

Credible paper ever.

This is very worth full and tells the truth about what’s happening in NGORONGORO now, and forecasting for livelihood of the local residents of NCA after the so called VOLUNTARILY RELOCATION.

I have been asking this question and no one ever answered.

Anyway! I appreciates about your worth full article with a naked truth about the Ngorongoro.

I honestly honored you for this RONALD B NDESANJO💪💪💪

It is real narates the truest story of Ngorongoro and Masai. For me I real appriciate the author for this paper and for who doesn’t undertand the real history of Ngorongoro Conservation Areab and Masai please go through it and you will thank the author!

A very refreshing read…

Well articulated

Ngorongoro conservation area belongs to all Tanzanians and not only the masai. Evictions have been done in several areas in Tanzania like in Buzwagi areas to give way for gold mining for the benefits of all Tanzanians. Who are the masai not to give way for tourism activities.

A thought provoking and well articulated article. I find NCA and its multiple land use practices a scam. Why? Its because the laws that establish NCA have lots of “claw backs”. Lots of constitutional rights are not within reach to the Maasai. People have the right to work and pastoralism is a livelihood activity. The mere act to tell the Maasai to reduce cattle herds limits their right to work. Lots of right-limiting examples can be highlighted in relation to the Maasai.

The maasai occupied the land before 1600s some literature suggest so. Might be the first