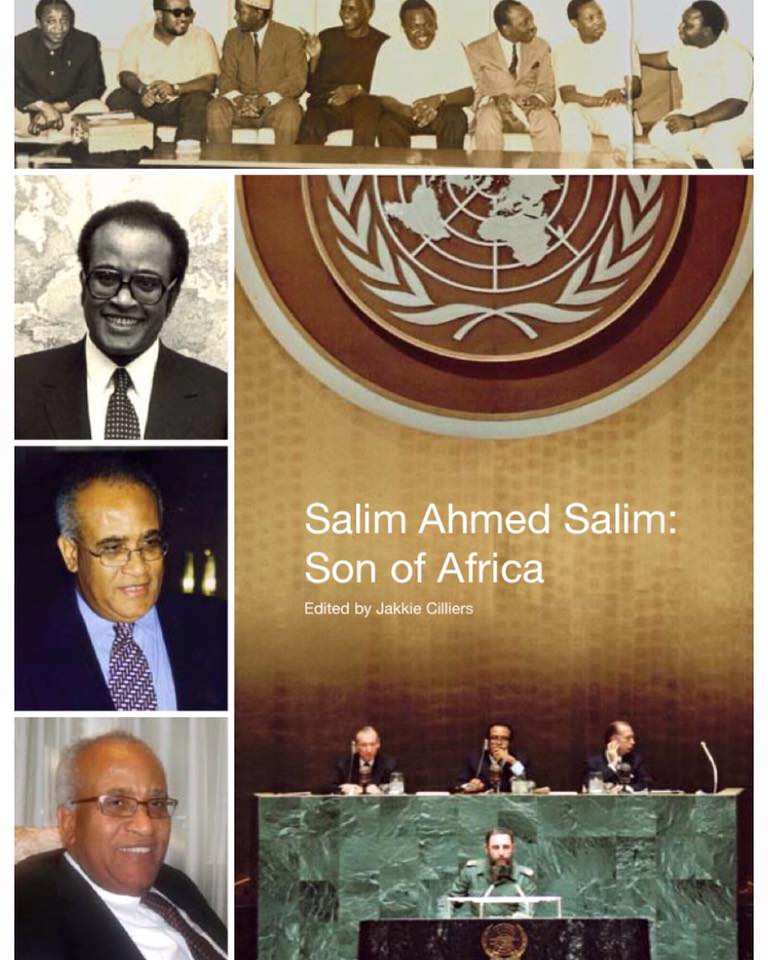

Book Review of ‘Salim Ahmed Salim: Son of the Soil’

Book Review: Professor Issa Shivji

Reading through these essays celebrating the life of Dr. Salim Ahmed Salim, I was intrigued by one fact. There is an uncanny convergence between Salim’s five decades of public life and the two important periods of Tanzania’s – even Africa’s – political history. Since his appointment as an ambassador in 1964, Salim spends the first five years picking his way down the diplomatic lane. Next ten years, he is his country’s top representative at the UN where he skillfully leads the diplomatic struggle for African liberation. These 15 years are also part of the post-independence nationalist period in Africa or the Bandung era of the Third World. This was undoubtedly a glorious period of recent African history, in spite of, or a wisecrack might say, because of, the Cold War. (Superpower rivalry allowed Africa to pursue its nationalist agenda with some consistency and vigour which would not have been easy in a unipolar world.) This is the era characterised by what the Chinese communists summed up as:

Countries want independence,

Nations want liberation,

People want revolution.

As chairman of the UN Decolonisation Committee, Salim leads the liberation struggle on the diplomatic front in the international arena. As chairman of the Frontline States, his mentor and role model, Mwalimu Nyerere, plans and guides the liberation war on the political front at the regional and continental level. There is admirable synergy between the two. Salim’s loyalty to Mwalimu is unquestionable. Nyerere’s faith in Salim is unreserved. But Mwalimu is a politician, a head of state; Salim is a diplomat, a loyal servant. Mwalimu could afford to call a spade a spade. At times, he would even exude anger, not to mention arrogance. Salim had to guard his language; he had to wear finesse, grace and elegance and, if necessary, even suffer fools. He could not afford controversy and avoided them. Yet, during his UN career he got into one, though not of his making.

Standing by his conviction, he adroitly and successfully led the move to get China its rightful place in the UN against the vicious opposition of the US. US would never forgive him. Garnering overwhelming support from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the South Pacific, Salim bid for UN’s Secretary-Generalship in 1981. He was consistently opposed by the US. The election process was repeated 16 times over five weeks. Salim’s grace intervened. He withdrew from the subsequent vote (see chapter 3). His UN career came to an end in 1980.

II

He spent the next decade – the ‘80s – at home, variously occupying different portfolios including foreign, defence and prime minister and later, during the second phase, as deputy prime minister. A diplomat had now turned a politician but did not lose his grace, diplomatic language and subtlety. He discharged his duties with unrivalled humility. Power did not go to his head. Madaraka hayakuvuruga akili zake. And for that reason, combined with his humility, Salim did not, nor did he try to stand out or stand above his colleagues. As a diplomat during his UN days, Salim worked in synergy with Mwalimu. As a politician, in the ‘80s Salim worked in Mwalimu’s shadow. Mwalimu’s last term (1980-85) was the most difficult period for the country, and for Mwalimu, as the country was plunged in a deep economic crisis. Salim silently and out of public glare used his good contacts and rapport to mobilise aid from countries like Algeria, Libya, Cuba, China, India and the Scandinavian countries (chapter 2).

The eighties decade was one of the most difficult period for Africa and for Tanzania. It was a “forced” transition from nationalism to neo-liberalism. Salim lived through that transition at home. Once again, true to his diplomatic élan, he avoids controversy. He did, though, get into one, but once again, not of his own making. After Sokoine’s tragic death, there is no doubt that Salim was Mwalimu’s preferred candidate to succeed him. In Mwalimu’s estimation, Salim had all the qualities to lead the country, including his Zanzibariness, since it was widely accepted that the second phase president ought to come from Zanzibar. Little did Mwalimu realise that there were incipient elements within his own party prepared to jettison his principles. Mwalimu consistently fought against ethnicisation and regionalisation of politics. But some of his lieutenants in the party were not of the same ilk. Salim fell victim to some parochial elements in the Central Committee who successfully maneuvered against Salim’s candidature. Unfortunately, the full story has never been told. I was hoping to see it in chapter two that deals with ‘Salim in Tanzania’. Unfortunately, my fellow scholars, Professor Mpangala and Dr. Shule skirt round it with a tantalizing sentence: “Recognising Salim’s experience, integrity and commitment many Tanzanians tried to persuade him to stand for the presidency in 1985 as he was Nyerere’s preferred successor” (p.40). So, what happened then? a reader would justly ask. The essay doesn’t provide the answer. We are left in the dark.

III

The ‘90s decade was the heyday of neo-liberalism. With the fall of the Soviet bloc countries, the world became unipolar. The end of the Cold War did not bring peace. It brought wars, hot wars. Within a decade, three countries lay in rubbles – Somalia, Libya and Afghanistan – and two more – Yemen and Syria – are on the brink of collapse. The militarization of the continent has gone apace with civil strife virtually all over the continent. It is in this situation that Salim returned to the diplomatic world, this time around at the head of the OAU. He remained at the helm of that continental organisation for 12 years – unprecedented three terms. The details of his activities and his relentless efforts to fight for peace on the continent are narrated in chapter four. I need not recapitulate them. I want to suggest that objectively Salim’s term at the UN must have been more satisfying then his twelve years at the helm of the OAU. For in the ‘70s, imperialism was on the defensive; nationalism and Bandung spirit were high. African and non- alignment blocs scored some significant successes at the UN. With all the challenges and frustrations, Salim’s diplomacy did pay dividends.

In the decade of the ‘90s, Africa faced a formidable single superpower. Even liberal and social-democratic governments in Europe had to toe the neo-liberal line. The Bandung bloc was much more differentiated than it had been in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Africa was liberated but not united. As chapter four shows, Salim constantly faced opposition from African states to his proposals for united African peacekeeping force. And the opposition was based on arguments of sovereignty just when the superpower and its allies were making mincemeat of African sovereignty. The most illustrative example is NATO’s refusal to let the African Union (AU) delegation led by President Zuma to land in Tripoli to attempt to reconcile warring factions. What appeared as worthy initiatives taken by OAU under Salim like ‘African-solution-to-African-problems’ or ‘responsibility to protect’ were turned on their head. ‘African-solution-to-African-problems’ was translated in practice to mean African soldiers fighting African militias on African soil financed by the US and trained by the Africom, eliciting even more terror attacks on African soil. The noble principle of responsibility to protect civilian populations against genocidal attacks irrespective of the principle of non-interference expounded by OAU under Salim was cynically used in Libya where NATO intervention was justified by R2P resolution of the UN. In spite of this difficult situation, Salim kept his fortitude and tried to carry out his mandate in dignity and in the best interest of the African people. No other person could have survived for three terms at the helm of OAU under such difficult circumstances.

IV

In 2001 Salim returns home but does not retire. He is called upon by various international organisations to lead peace missions. One of the most difficult was the one in Darfur. It would have been fascinating to have a chapter in the book on his work in the Darfur mission. Unfortunately, there isn’t one. I guess the editors must have been overwhelmed by Salim’s prolific work – they had to make choices.

On the home front, Salim, the humble diplomat, has again consciously tried to avoid controversies. But he got into one, this time of his own making! In 2005 he offered his candidacy in the presidential race. He successfully got through the organs of the party being among the three candidates presented to NEC. It was not easy. Tanzanian politics had undergone a sea change since Mwalimu. No longer the politics were clean or principled. He faced “vicious” campaign to tarnish his name, including rewriting of his historical record and doctoring of his 40-year-old photographs. But Salim never abandoned his dignity and decency.

He didn’t retaliate in kind. During the lobbying for NEC votes, his campaign team had strict instructions not to indulge in any malpractices. (I know this from an internal source.)

But he didn’t make it. Changing of goalposts ensured that he wouldn’t go through. ‘How could he’ I asked myself, ‘if he couldn’t during Mwalimu’s time?’ Again our authors of ‘Salim in Tanzania’ avoid discussing this episode.

I am of course aware and appreciate that these essays are celebratory. But in my view, it does not mean avoiding the controversies and adversities that your subject faces in his lifetime. It is precisely in such situations that the fine character of your subject comes out, as it did in Salim’s case. He came out of the fight for UN headship gracefully and with dignity. To this day Chinese visitors to Tanzania, including presidents and prime ministers, pay him a visit. They have not forgotten the role he played in the admission of that country into UN. Again, in the two controversial situations at home, he kept his dignity and personal integrity. But he must have been pained by the parochial – racial, ethnic, religious – trends in our politics. He made a mental note of it and extracted it in his 2014 speech thanking AU for honouring him. (reproduced as chapter 5).

Perhaps drawing from his own experience but also witnessing what is going on in the continent, he warned, again in his typical diplomatic parlance:

The issue of systemic economic and political alienation of the majority of the African people that comes with the impressive record of economic growth and democracy has led to considerable tension in countries – tension between urban and rural, tension between ethnic groups, between the rich and the poor, between the security groups and the people, and even more worrisome tensions across religious lines.

The warning is timely both for the continent and for Tanzania. These fault lines are indeed becoming intense and can easily lead to fragmentation of our societies. This is where we, the intellectuals, need to focus, analyse and expose and condemn politicians who are using the fault lines in their own narrow interest.

Needless to say, I recommend the book and hope its gaps will be addressed in the second edition.

Salim Ahmed Salim is truly a son of the Pan-African soil. May he live long to continue his pan-African ambassadorship.

Sons Of The Soil is an upcoming sports documentary series. The series will be taking us behind the scenes on the journey of the Jaipur Pink Panthers, a pro kabaddi team owned by Abhishek Bachchan. It is being produced by BBC Studios India and directed by two-time BAFTA Scotland Winner Alex Gale.sons of the soil release date