My inner struggles to come to terms with what has been going on in my country took me to this article titled, Anti-intellectualism, Chinese Style. It was from it I was inspired to write this piece. Richard Hofstadter defines anti-intellectualism as the resentment and suspicion of the life of the mind and of those who are considered to represent it. According to him, the part of the mind that examines, ponders, wonders, theorizes, criticizes, and imagines is what is called intellect.

Intellect is thus the critical, creative, and contemplative side of the mind. An intellectual, therefore, is someone who possesses and exercises these traits.

Anti-intellectualism is often a foursome intercourse, other bedfellows being conservatism, religious fundamentalism, and populism. One must add, it flourishes under authoritarianism. It is a global phenomenon, so Tanzania has not been an isolated case. But, certainly, actions and consequences of anti-intellectualism vary from one country to another.

In Tanzania we have experienced all the above, especially in the last 5 years under an authoritarian populist leadership. In that spell, criticizing the government was likened to betraying the country as a new wave of bloated patriotism swept the country. Make Tanzania Great Again (MATAGA) became an expression of this new form of patriotism, strangely inspired by Donald Trump’s maxim of Make America Great Again (MAGA).

This went hand in hand with excessive moral policing, as religion and ‘Tanzanian culture’ were used to stifle freedom. Tanzania is a deeply superstitious society (here I also mean religious). Consider the killing of albino,and the persecution of elderly women in the country, all done for superstition. In 2011, thousands of people including prominent politicians trekked to a village in Loliondo to drink from a ‘miracle cup,’ believed to cure chronic ailments. The eventuality, of course, was that there was no miracle and the ‘medicine man’ has slid into ‘oblivion’ since then.

Our collective inability to critically engage the mind has legitimized swindlers who masquerade as sellers of hope. These types are a passionate lot and quite motivated. Their equally, if not more, determined faithful has led someone to refer to them as motivated idiots. And they are ubiquitous – found in houses of worship, workplace, and, worryingly, the political space.

A former Member of Parliament (MP) once likened a section of fellow parliamentarians to an imbecile who when asked, “are you hungry?” his answer was yes. “Are you full?” his answer, again, was an emphatic yes! It was a scathing criticism directed at the rubber-stamping MPs who complain about the government’s poor performance yet accept its every motion and action.

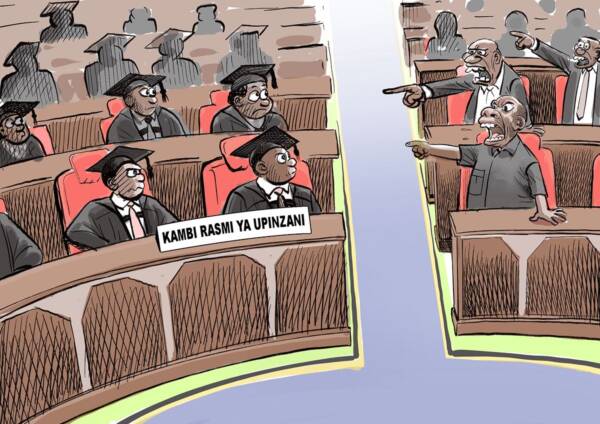

Recently, the anti-intellectualism in the house of the legislative body has taken a new turn with skirmishes between the “educated” vis-à-vis the “less educated” MPs. One cartoon depicted a frantic scene portraying the educated MPs to be the new opposition in the House, after they were on the receiving end of stern criticism from their ‘less educated’ counterparts.

As anti-intellectualism occupies mental faculties, our experts and intellectuals are having a difficult time staying relevant. How can they justify their existence when our systems are broken, and they are the ones expected to fix them? Yet, given how some have carried themselves, the resentment against them is not without merit.

Our experts and intellectuals have at times turned into caricatures only good for entertainment at best, or outright corrupt, enablers of corruption, and accomplices to tyranny at worst. Even some academics who essentially earn a living for thinking, have become anti-intellectuals themselves. When it matters most, they have succumbed to pressure by kowtowing and bending over backwards to please the powers that be. This flattery has earned a new vocabulary in Tanzania’s cyberspace – chawacracy.

The resentment against these types, while understandable, poses great risks ahead: it will not end with the experts and intellectuals as persons but expertism and intellectualism altogether. Already, a culture of anti-science and post-truthism is burgeoning before our eyes.

However, there is a rejection of experts and intellectuals that is unmerited. This is especially when populism reigns, making expertism too costly to pursue in the eyes of politicians. In this context, expert opinion that contradicts the politics of the time is not welcomed.

When, for instance, a deputy health minister who is a microbiologist warned in 2020 against steam inhalation as a possible COVID-19 treatment, he was dismissed a week later. The same month saw the head of the national laboratory suspended, chiefly because the COVID-19 test results were exceedingly positive someone had to put a stop to it. It was a déjà vu because the Director General of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) was fired in 2016 after she had released a report showing the country had cases of the Zika virus.

Interestingly, such decisions to punish those who dared to examine, ponder, and criticize were usually celebrated. When the head of the national laboratory was suspended, propagandists moved in quickly to propagate the idea that she was being used by mabeberu (i.e., imperialists – Tanzania’s real and imaginary enemies) to taint our country. Similar mebeberu card was at play in the firing of the NIMR boss, this time by the then president himself. In the last five years, we have also witnessed this anti-mabeberu rhetoric being used to rally the country behind an authoritarian leadership.

Facing the prospect of being converted into public enemies, some experts chickened out, leaving whatever is left of their dignity at the mercy of those in positions of power. The results have been catastrophic. Consider, for instance, the construction of the Dar es Salaam’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) workshop facility, built in one of the most flood-prone areas of the city. It now needs relocation. It has since been learnt that the construction was against the recommendations of the National Environment Management Council (NEMC).

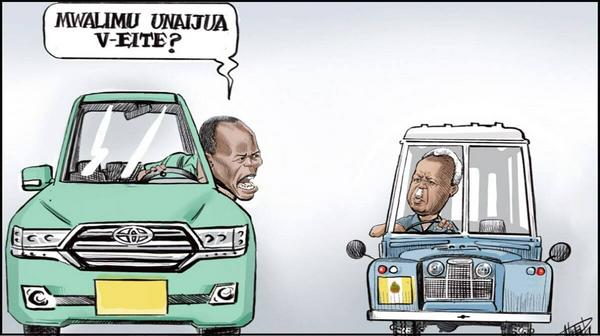

If that does not cut it, consider this: the late President Magufuli is involved in a duel with an engineer over the installation of a lift in a hospital building. He probes why the building needs a lift, to which the engineer explains that it’s a requirement of the law that all public storey buildings must have lifts.

But the then president, probably occupied by thoughts of austerity and/or resentment against the expert, is having none of it. He ends up insinuating that the lift was unnecessary! Credit to the engineer who firmly stood his ground to the very end.

The ex-president was also quoted elsewhere, castigating environmental and occupational safety organs for ‘putting investors off.’ “God created this land, but you hear these environment and safety experts say it cannot be used for this or that purpose,” he wondered (translation mine). This rejection of elite institutions as well as those categorized within the social and/or intellectual “elite” (e.g., professors) is what Daniel Rigney calls populist anti-elitism.

Rigney’s other type of anti-intellectualism is religious anti-rationalism (rejection of reason, logic, and fact in favor of emotions, morals, and religious absolutes). Tanzania is probably all the time more religious than ever. As a society, we have failed to provide answers to our misery such that the only thing that makes sense is superstition. We virtually assume everything that comes our way is God’s plan. The latest episode of this religious dogmatism was on display in 2020 when the nation was urged to fight COVID-19 with prayers!

Mwalimu Nyerere once said it was not TANU’s mandate to pave heaven paths for Tanzanians, in response to the Church’s reluctance to embrace Ujamaa and villagization policy. Now it appears this rationality died with him.

Across the political spectrum, political parties and government leaders alike are campaigning for our admission into heaven. At times one could be forgiven for mistaking a politician for a preacher. Former Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner, Paul Makonda, for instance, took it to the altars to seek God’s intervention in saving his people from, among other purported ‘evils’, homosexuality.

Religious leaders grace every state occasion. They have probably been in the alleys of the State House more than most senior government officials. Eager to reciprocate the trust shown in them, they have gone out of their ways by, for instance, organizing prayer sessions for the release of a state-owned aircraft that was confiscated in South Africa over an unpaid debt.

The COVID-19 pandemic has in particular exposed the anti-intellectuals in our midst. Encouraged by the government’s position on the disease, which until lately had been a mixed-bag of denialism, tiptoeing, and acceptance, anti-intellectuals have found a new zeal. They are terrorizing the public with conspiracy theories, including that the virus is a laboratory invention to kill Africans!

Despite a global scientific consensus on the efficacy of some COVID-19 vaccines, we are being warned of how the vaccine in general will temper with our genetic makeup. This is quite convincing even for the educated, except that it comes from someone who built his ‘reputation’ from raising the dead. The fact that that individual is now a Member of Parliament is yet another proof of our collective imbecilization.

In addition, the clever among conspiracy theorists are pushing the narrative that ours is a God’s favorite nation, that’s why we have been spared from the full impact of the pandemic! You hear this stuff being spewed by politicians, men and women of God, and the fairly educated among your close associates at the time when people were burying their loved ones at an unprecedented frequency due to ‘respiratory challenges’ – a politically correct name for COVID-19. The mere mentioning of COVID-19 was tabooed, even for medical practitioner.

It took the Church to start preaching science when the government was indulging in preaching divine intervention for the day of reckoning to come.

Unreflective instrumentalism is Rigney’s third type of anti-intellectualism. Accordingly, this is a belief that the pursuit of theory and knowledge is unnecessary unless it can be wielded for practical means such as profit. Many times we hear those who seek and acquire knowledge being ridiculed for not being ‘successful.’ The sanctity of knowledge is reduced to material possession or position of power.

It won’t be easy to arrest anti-intellectualism in our country. But the solution must come from an education, which popularizes science and critical thinking. At home, we must instill confidence in our children by encouraging them to ask questions. Our children should be allowed to fully live the life of the mind. A competent political leadership with a scientific inclination on issues will be of great help in this noble endeavor.

May the relatively new leadership in Tanzania take up the challenge.

Copyright

Thanks, you have done

Thanks for taking your time to read it.

I can really see conservertist overview of the article as opposed to sceptist, and more pesmist inclination as opposed to optimistic kind of judging the whole idea of anti-intellectualism. However, well narratated in the said regards.

Great analysis!

Thanks, Ansbert.

I’m impressed by your creative molding if events to send a not so common message! An absolute stunner in my opinion. Great article, thank you!

Uchambuzi mirua sana! Michoro ijachekesha ilihali ikikuliza sawia. Kazi nzuri sana kaka Shangwe!

Wow, well explained. We need to teach our children not to be scared of change and also to be inquisitive.

Fear is a bad thing, people act out of what they believe beacause of fear. They priotize their interests in place of anything thats why we have these complication.

Everybody expect something from the rulers whether our elites or religious leaders try at the best do dance with the existing whistler. They are inconsistent of what they believe, they are not bold at all. Infact they are ready to sell their pride at any reasonable price.

However it demands high sacrifice to stand on your standards, in Tanzania, I think people act in the pattern against what we expect for self-protection.

A religious leader will support what the ruler want to hear not what he suppose to. Our systems need to be changed: new constitution is needed

Thanks for contributing to this discussion. Indeed there’s work to be done.

What a great story

Great, relevant, thought provoking article. Congrats

Thanks for taking time to read it

Good work

Thanks

A very informative and logical article. Bravo!!

Excellent piece of work! Congrats Dr Shangwe.

A piece of work that one should share his/her time to fully engage in.

I hope one won’t be condemned to “anti-intellectualists” dangeons by disagree with some of the the issues raised in the article.

All in all itsa good work

Amazing

Thanks for taking time to read it

Good analysis with a great challenging of outthinking observation of the future national carrier.

Thanks for taking time to read it

Best article, summed up alot in a nutshell

Thanks, Michael

This is a superb article. I enjoyed every part of it.

Thanks, Shirumisha.

When a social organization (country) chooses a careless unorthodox tact and the jungle trajectory to pursue matters-science (natural or otherwise), political, economic…etc., in a fashion that our beloved social organization did or has been doing, it therefore concedes that, indeed, is in a state of “imbecillitatem” (imbecility).

Thanks for taking your time to read it

It needs a great and active mind for an intellectual person to create such a wonderful thinking that ends up on a concatenational writing, congratulations!

Thanks, Sima.

I experienced this first hand while working. Most Tanzanian shy from asking difficult questions. They don’t want to annoy the “boses” in most organisations. I also noticed that those who were brave enough to question certain decisions at work were not tolerated. They were the first to be shown the door during retrenchment exercises.

Thanks for sharing your experience on this discussion, Janet.

I can really see conservertist overview of the article as opposed to sceptist, and more pesmist inclination as opposed to optimistic kind of judging the whole idea of anti-intellectualism. However, well narratated in the said regards.

Our education system does not create critical society.

Intellectual themselves fails to protect intelectualism.

Good analysis!

Rich analysis delivered in a creative and refreshing voice. So much to ponder, think and connect with this piece. I find the phenomenon of seeing a thing like Corona or corruption and plainly denying its empirical existence quite fascinating. Where does it come from and what kind of work does it do for politicians and the public alike? I laughed when you said the government and some members of the church have switched sides! The Church, some of course, now embraces science more dearly than the secular state. Galileo must be smiling wherever he is.

A good thought

I have read this from Ghana, and if one inserted Ghana wherever Tanzania is, the article would still be perfect, minus a few specific examples. “What do you have to show with your big English?” is a common question often used to counter intellectuals who speak up against rubbish spewed by dimwits with cash.