A Farewell Note to the Neoliberal Academy *

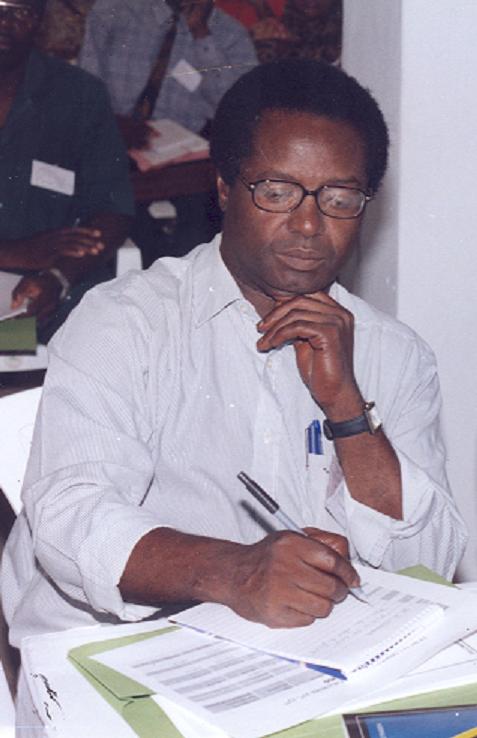

By Professor Chachage Seithy Loth Chachage

I leave the self-proclaimed “World Class University” without regrets, since I have gained more experience and knowledge. I now understand better James Baldwin when he said the greatest danger facing humanity today is the tendency to forget what is humane in us. Why then am I leaving? Some may wonder. Since it is said that truth sets people free, I am personally against crocodile tears. Therefore, I ask for your indulgence if I will be compelled to pull the carpet under some people’s feet, I plead that I be forgiven for that.

It was the excitement to participate in the African Renaissance and transformations that fired me to agree to join the university. My hope was that I would stay for at least three to four years. For me it was a challenge to be part of a body of critical intellectuals, socially responsible and competent besides being a moral authority given the history of anti-apartheid of this university.

I believed I was joining a community ready to defend the ideals of social justice. And of all the disciplines, sociology has always stood for that. To my chagrin, I found myself having to make a decision to pack my rucksack and go back to Tanzania within a few months: my camping here had become a nightmare to a few individuals.

If I had not come here at all, my knowledge of South Africa would have remained bookish, partly informed by the encounters I had with the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan African Congress (PAC) freedom fighters that were in Tanzania for many years. I still remember, for example, the talks given – while I was at high school – by the late Gora Ibrahim, Oliver Tambo, Joe Slovo, Govan Mbeki and many others.

In those years we read Nelson Mandela’s famous speech at the Rivonia Trial as part of our high school requirements. As high school kids, we also read Chief Albert Luthuli and Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe. Some of these were our supplementary materials for anybody pursuing literature, even though these were not artistic pieces as such. But we also read Alex La Guma, Peter Abrahams and Lewis Nkosi.

We learnt the social history of Africa (including South Africa). That was besides American and European history. That was in high school. We all became convinced by then that Africa was one and the Internationale was the future of the human race!

What I encountered after my arrival at the university is not what I had been made to believe. Within less than a month, I discovered that what I thought was an inspiration in the beginning, was caused by the fleeting moment. The inspiration was a self-deception justified by the so-called vocational calling. My hope to contribute better than my best in the knowledge ‘industry’ was an illusion.

I was even dictated to about the content of what to teach in the course that I was assigned. This was done on the pretext that the university was introducing programmes, which were supposed to respond to job markets and global dictates. Therefore, of paramount importance was the imparting of “skills”, as an important element in the transformation of higher education. **

A successful academic, under such circumstances, naturally, is not one whose research is “acceptable” to his or her profession or relevant to human needs, but one whose research is capable of attracting the greatest funds or controls a research institution capable of distancing itself from the purely teaching structure of the faculties and departments. Financial sponsors are the ones who determine the form of knowledge; and accepted knowledge, in turn, is increasingly that of “research technicians” or “professional researchers” rather than scientists. For these ‘academic entrepreneurs’, the definition of knowledge has increasingly been restricted to ‘specific practical concerns’ and the so-called ‘pragmatic’ teaching of programmes and research.

Thus, because education is geared towards the market, students and even lecturers (I would add) do not have reading and writing habits, except for utilitarian or bread and butter questions! That is to pass examinations, to get a job or a promotion. Nobody wants to go beyond the classroom materials! Important to note here is the fact that the so-called response to the “market forces” and “global forces” for some of the academia is nothing more than an ideologically determined position, which would like to turn the university into a supermarket without any long-term considerations of the national and societal needs in general.

My biggest folly was to raise queries on institutional and academic matters and specifically on the so-called new programmes. When I initially questioned the assumptions behind ‘transformations’ in education soon after joining the university, a ‘colleague’ cautioned that I it is unwise to look negatively at the government’s good intentions. Armed with hindsight I can now state boldly that I was too old fashioned, wishing that transformations and the so-called ‘new culture of knowledge’ could be complemented by the old age culture of learning with humility. ***

After raising the queries I discovered that I was simply a ‘development post’ (to redress the racial imbalance and not the intellectual one!), and therefore, not the right material for a “World Class University” – the only one in the world, which proclaims to be so. Not even Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard does so. But then, village community – those village philosophers have an adage that goes: “It takes a fish out of water to make noise that it lives in water!”

When I found that my continued efforts to raise issues did not yield much by way of resolution, I finally remembered a poem that was quoted by Peter Abrahams in A Wreath for Udomo: “Did you think victory is great? Yes it is. When it cannot be helped, defeat and dismay are great!” I decided to tender my resignation. Meanwhile, I decided to spend my time learning more about South Africa, and the other stuff that I had taken for granted previously, when I held the naïve view that human nature cannot be so depraved.

I leave the university enriched and more experienced. As the rural philosophers of my humble background say: “To travel is to learn: no experience is ever useless”! I am going back to Tanzania to those people who taught me the virtues of all sided knowledge. To those who still hold the view that knowledge is more important than wealth and power. To paraphrase the late President Mwalimu Julius Nyerere of Tanzania: ‘Better live in poverty with dignity than in wealth as a slave.’

——————

*This article is primarily compiled from the following unpublished sources: ‘A Farewell Note at a Tea-Party organized by Sociology Department, University of Cape Town’ (28/06/2000) and a Public Talk on ‘Academic Freedom and Social Responsibilities of Intellectuals: Some Thoughts’ (29/09/2000) organized by the University of Dar-es-Salaam Academic Assembly (UDASA) in collaboration with the Dar-es-Salaam Philosophy Club (DAPHIC) and the Dar-es-Salaam University Political Science Association (DUPSA).

**This paragraph is drawn from ‘A Curtain Raiser’ in Chachage Seithy L. Chachage’s (2000) ‘Environment, Aid and Politics in Zanzibar’, published by the Dar-es-Salaam University Press (DUP).

***This paragraph is improvised by ‘But you are Free to Teach the Determined Content!’ which is the first section of Chachage Seithy L. Chachage’s (2004) ‘Higher Education Transformation and Academic Exterminism: The Case of South Africa’ in Tade Akin Aina, Chachage Seithy L. Chachage & Elisabeth Annan- Yao’s (eds.) ‘Globalization and Social Policy in Africa’, published by the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA).

Andiko hili lina maneno mazito sana. Je, nchi yetu inawaenzi vipi wasomi kama merehemu Chachage and Haroub Othman?

Je, mawazo yao na kazi zao zinaendelezwa kivipi?

Kuna hatari ya kupoteza historia za wana fikira hawa kama sababu za makusudi hazitachukuliwa kuwaenzi na kuhifadhi maandiko yao.

Mdau

Faustine

Umenikumbusha mbali sana,hasa hapa kwenye utamaduni wa kujifunza, ni mgogoro kwelikweli kwa tuliowengi ila sasa matakwa ati ya soko ndio yametawala kwasasa tena nadhani zaidi na zaidi

Ahsante sana Prof. (R.I.P) kwa hii elimu.

What comes to my is revolutionary poetry but also a kind of post-colonial disenchantment: we are free as Africans; we will change the order of things; restore our dignity and place in history. Many years later Professor Chachage colleague Mamdani writes about consultancy culture basically intellectuals for hire.

Tafakuri mujarabu hata leo.

R.I.P Brother Professor Seithy Loty Chachage Mwani…