How good is the deal between Barrick and the Government of Tanzania?

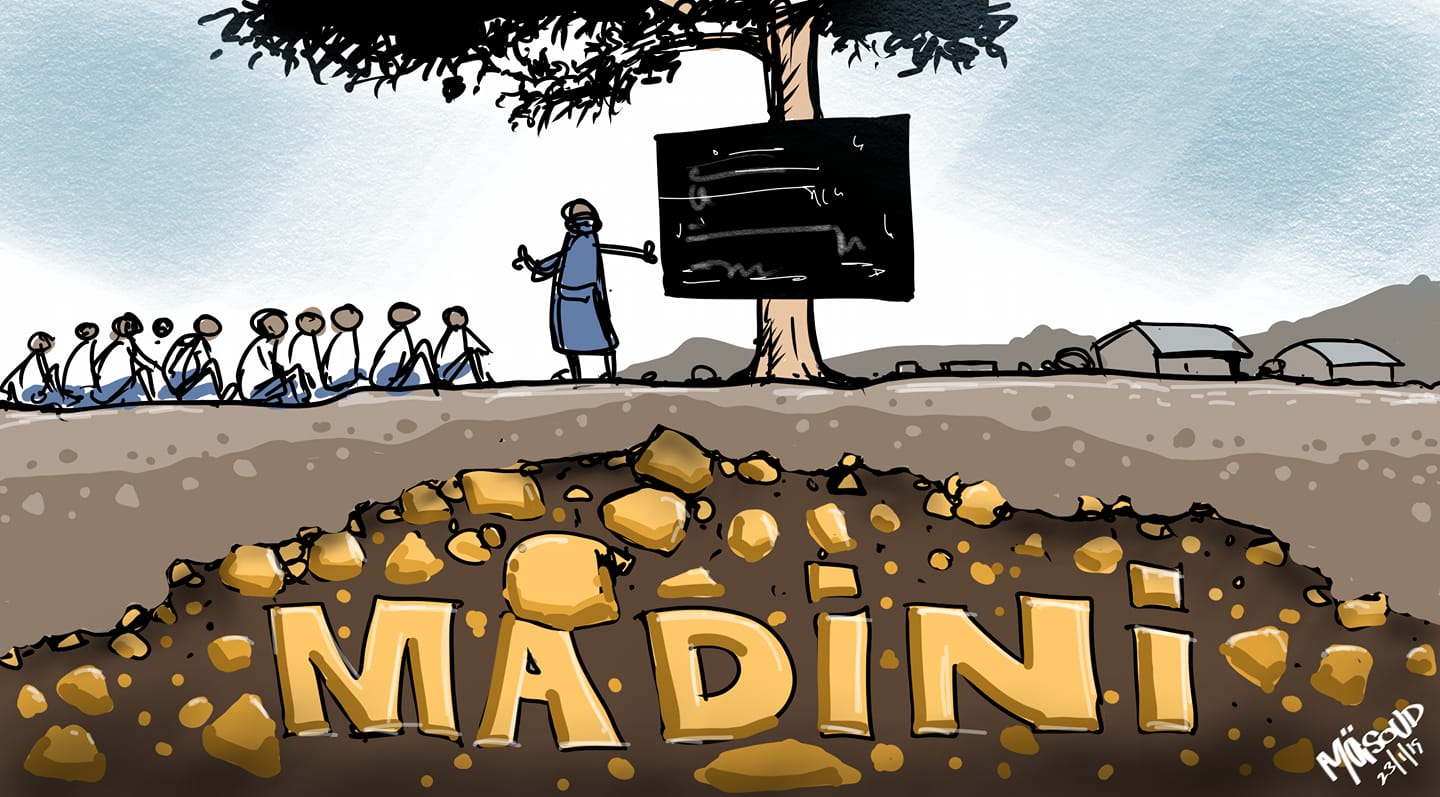

Dastan Kweka

The Government of Tanzania and the mining giant – Barrick Gold Corporation – have finally entered into an agreement that, if implemented fully and smoothly, will settle more than two years of a bitter confrontation between Barrick’s subsidiary – Acacia Mining PLC, and the eastern African nation. In Mid July, Acacia disclosed a draft agreement containing the proposed terms of its acquisition by Barrick, and thus sent a signal that a breakthrough had been achieved, after nearly a year of disagreement, and resistance.

The “recommended final offer” that was disclosed in July provided for the terms of acquisition of Acacia`s shares – about 36% – that weren`t already owned by the parent company, as a mechanism for buying the subsidiary out of Tanzania, and thus ending a protracted business stalemate that the subsidiary had grappled with since, at least, early 2017. Now that the agreement between Barrick and the Government of Tanzania has become effective, stakeholders can take time to reflect on the lessons that the country might draw from a heroic attempt to capture a fair share of benefits from its growing extractive sector.

The “recommended final offer” that was released to shareholders by Acacia, for information and consultation purposes, included an overview of the framework of Barrick`s agreement with the government of Tanzania. The content of the framework (though the final version may have changed slightly) can be seen as symbolizing the extent to which the Government of Tanzania, through its mysterious negotiation team (GNT), was able (or unable) to make, and defend its case. This article draws, in part, from that content, and other associated developments. Before examining the terms of the framework agreement, and the lessons that the entire confrontation can offer, let me highlight, albeit in passing, a background to the rift between Acacia Mining PLC, and the Government of Tanzania.

Overview of the GoT – Acacia rift

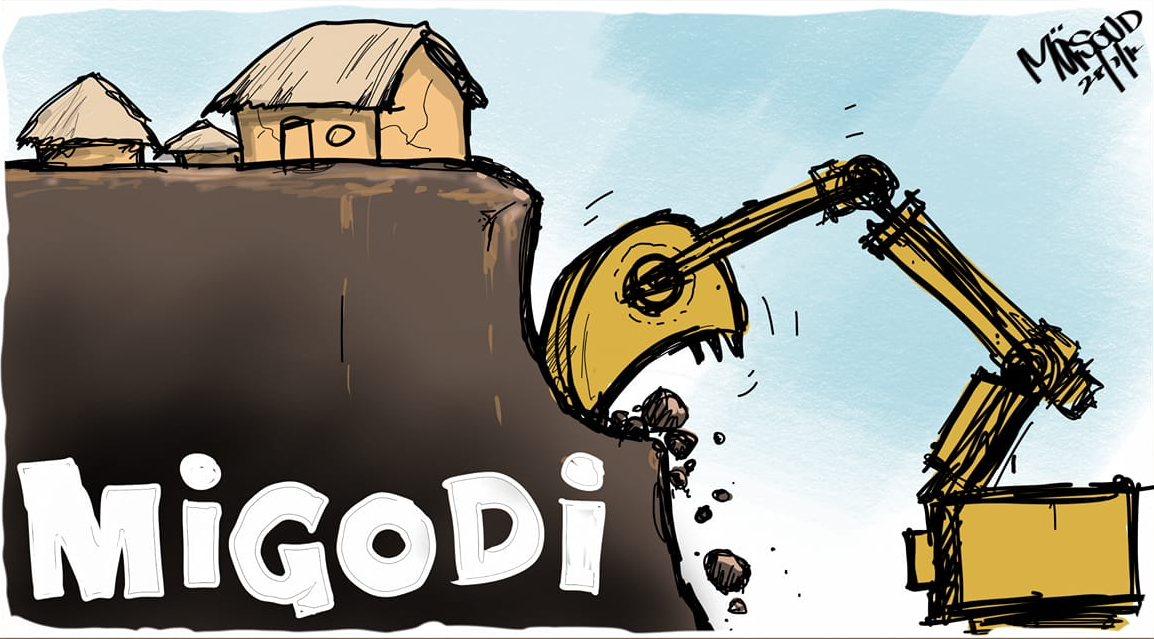

Conflict between Acacia and the Government of Tanzania (GoT) worsened in early 2017 when public authorities, acting on orders from the state house, barred the company from exporting a consignment of about 277 gold/copper concentrates containers. This decision was followed by formation of two Presidential committees – the first (also known as Prof. Mruma committee), was announced in March, 2017, and tasked with investigating the type and quantity of the minerals in the containers, while the second (Prof. Osoro committee), which was established in the following month, was given a quite broad mandate. It looked into the legality of the entire gold/copper concentrates export arrangement between the government and Acacia, and sought to determine if the government was receiving its fair share of revenues. This task included reviewing the respective contracts and advising the government on necessary improvements. The committee was also required to determine the number of mineral sand containers that had been exported between 1998 and 2017, provide an estimate of revenues that the government was entitled to obtain, and compare that with what was actually received. The difference would, eventually, constitute a huge debt that Acacia would be asked to settle.

The findings of both investigations are (now) well known. The first committee, which also investigated the conduct of the Tanzania Mineral Audit Agency (TMAA), a public entity that was responsible for inspecting and certifying mineral sand consignments for export, claimed that there was a high quantity of gold, and other valuable minerals – copper, silver, iron, and sulphur – than initially declared by Acacia, and that the government of Tanzania was losing billions of money in revenues. As if that was not enough, the committee added that, the value of iron, sulphur and “strategic minerals” was never considered in royalty calculations. TMAA was seen as incompetent or complicit (or both) – its fate was sealed. As expected, Acacia disputed the findings, citing “more than 20 years of data available” to them, and called for an “independent review of the content of the concentrates.”

The second committee argued, in its findings, that Acacia had neither been registered in Tanzania nor obtained a certificate of compliance from local authorities, as required by the law, and while the company claimed to own three subsidiaries in the country, no documents proving ownership or interest in any of them had been submitted to authorities. As such, the company had not qualified to receive a mining license and could not (legally) engage in mineral business in the country. Government of Tanzania would, subsequently, stick to this finding in refusing to engage Acacia, and instead, preferred to negotiate with its parent company – Barrick Gold Corporation. Apart from the registration status of the company, the second committee accused Acacia of under-declaring revenues, and thus denying the country huge sums of resources. The company, in its defiant response, disputed these findings too, citing its supposedly huge archive of data which, allegedly, showed a different revenue trend. It is this disagreement between Acacia and the GoT that makes the terms of the framework agreement between Barrick and GoT interesting, and worthy of analysis.

A humiliating defeat?

The “draft” agreement between the GoT and Barrick that was released in July, and became operational in September, included a caveat that there were several “substantive” issues that had not been settled, and that the final deal would, possibly, be significantly different. Although the final agreement is not public, it is logical to assume that any subsequent adjustments did not radically alter the key foundations of the deal (the agreement became effective two months after it was disclosed – an indication that it’s foundations remained intact). As such, it is safe to use the public version of the framework agreement for analysis purposes.

An examination of the framework agreement reveals that the government of Tanzania agreed to a, surprisingly, quite far-reaching agreement – “a comprehensive settlement of all disputes between the GoT and the Acacia Group” – whose effect will be to “release and forever discharge one another (and their respective related persons) from all and any Claims that they have ever had, now have or hereafter can, shall or may have against one another or their related persons …” (see page 72). In other words, Barrick negotiated so hard to ensure it did not inherit a single dispute or liability from Acacia. With this clause, years of public complaints about human rights abuse, unfair compensation cases and concerns over environmental pollution that had been raised against Acacia were extinguished – just like that!

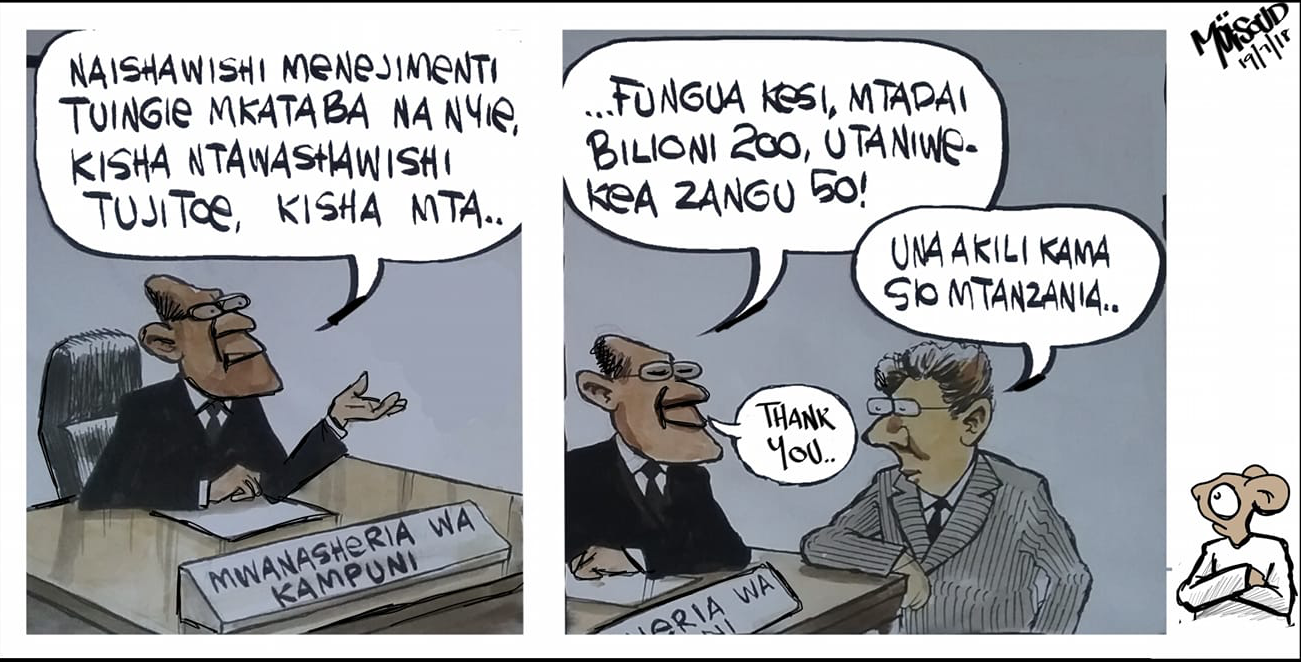

The framework agreement also indicates that the government was unable to prove or sufficiently defend any of its substantive accusations against Acacia. For instance, one of the key assumptions under the “settlement terms” of the deal reads, “neither party admits any liability or wrongdoing whatsoever.” (see page 73). This points to a mutual compromise that was, most likely, induced by a serious deadlock in negotiation, and reaffirms doubts about the credibility of the evidence gathered by the two (Mruma & Osorro) Presidential committees. Also, the assumption gives a clue as to why a $190 billion tax bill imposed on Acacia was later reduced to a mere “aggregate sum” of $300 million, to be paid in six installments, “in consideration for the full, final and complete settlement of the disputes and liability to taxation…” Below is a summary of other key provisions from the agreement;

A key setback regarding the “50/50” split is its broad definition as indicated in the table. Such a broad definition contradicts what Prof. Kabudi communicated (watch from 0.55) to the nation in October 2017 when he sought to clarify what seemed to be the agreement at the time. He stated that the 50/50 split would come from profit minerals (after companies had paid all statutory taxes i.e. royalties, corporate income tax etc). In the end, Kabudi accepted a formula he had initially rejected.

The following are few observations from my analysis of the agreement;

– It seems that the spirit of the agreement, from the government`s point of view, was to draw a line under all that had happened (possibly after a deadlock in negotiation). Expelling Acacia was a key step in initiating a “new” (though rough) start. This has been the only clear victory to date.

Notably, confrontation with Acacia raised the profile of the country as a risky place to invest in, and it may take a while before we realize the full scale of the consequences arising from negative coverage that took place across the world.

– A deadlock in negotiation must have emanated from a disagreement over data on mineral composition as well as production trends (and subsequent difference of opinion on tax implications). Acacia had questioned the findings of the first committee, as soon as they were released, and there is no indication that the company changed its position. Surprisingly, some “former” TMAA officers were aware that the findings of the first committee, especially on mineral composition, were highly questionable, but nobody was willing to listen to them (they were suspects, after all). I still think that the decision to disband TMAA, and not use its officials in pursuing the case was wrong. TMAA had built its capacity over the years, through “learning by doing” and should have been reformed, not disbanded.

– It is clear from the agreement that Barrick representatives (most likely acting on instructions from Acacia) sought to clear the names, and secure the release of (Acacia`s) former employees as well as associates that got into trouble following a deterioration of the business relationship (see page 72). Beneficiaries will most likely include Deo Mwanyika, and Asa Mwaipopo – both of whom are languishing in jail. But will they be required to plead guilty in return for amnesty, as has been the case with those accused of economic crimes? This will be the first, significant test to the agreement.

It is important to note that the agreement is (though rightly) silent about how the government will treat its own citizens that were caught in the net, either for being considered complicit or incompetent (or both). Former employees of the Tanzania Mineral Audit Agency (TMAA), some zonal mining officers, and others, that were roughed up, and/or detained, deserve restitution. It`s hard to see how a case against any of them will stand, in light of the huge concession that the government made in its negotiation with Barrick.

So how bad is the deal?

Analysis by Haki Rasilimali, a network of CSOs working on natural resource governance concluded that the agreement was “a bad deal that will leave Tanzania worse off than before.” ACT Wazalendo, a vibrant opposition party has also questioned the content of the agreement, as well as the manner in which it was reached i.e.; parliament was left in the dark, even though it was central in passing tougher legislations in 2017.

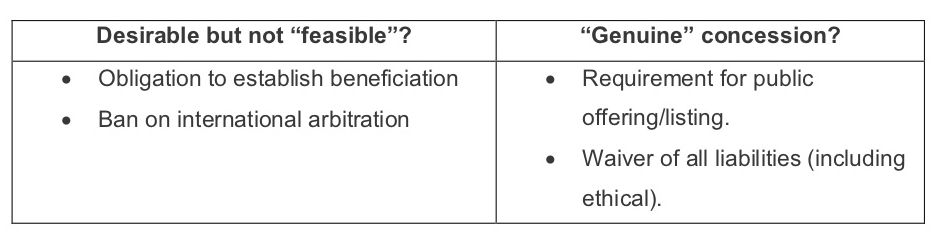

Both analyses combined a reflection on what the government promised but failed to achieve, possibly for feasibility reasons i.e. $300 million upfront payment, construction of smelter (cf. news about Tanzania awarding licenses for the construction of a mineral smelter and two gold refineries to Chinese firms), permanent ban on export of concentrates, as well as allowing International arbitration (contrary to a law passed in 2017), with “genuine” concessions such as waiver of obligation to float shares in DSE (though the feasibility of this could also be questioned on the basis of weak local purchasing power). This combination means that the analyses failed to discount what was not feasible, and achievable (and which ends up skewing their conclusions). Most importantly, the analyses do not acknowledge the limitations arising from the apparent government failure to prove its case.

To undertake a reasonably balanced analysis, one has to separate what was considered desirable but possibly not feasible, from “genuine” concessions. Below is an attempt to do so;

A close examination of the agreement between Barrick Gold Corp and GoT points to a possibility that the deal might be fairly good, in light of the indication that the government failed, though heroically, in proving it’s case i.e. that it was being short-changed. To be able to say, with certainty, whether this was a bad deal or not, one will have to model the results, or wait for clues in EITI reports. For now, the jury is (still) out!