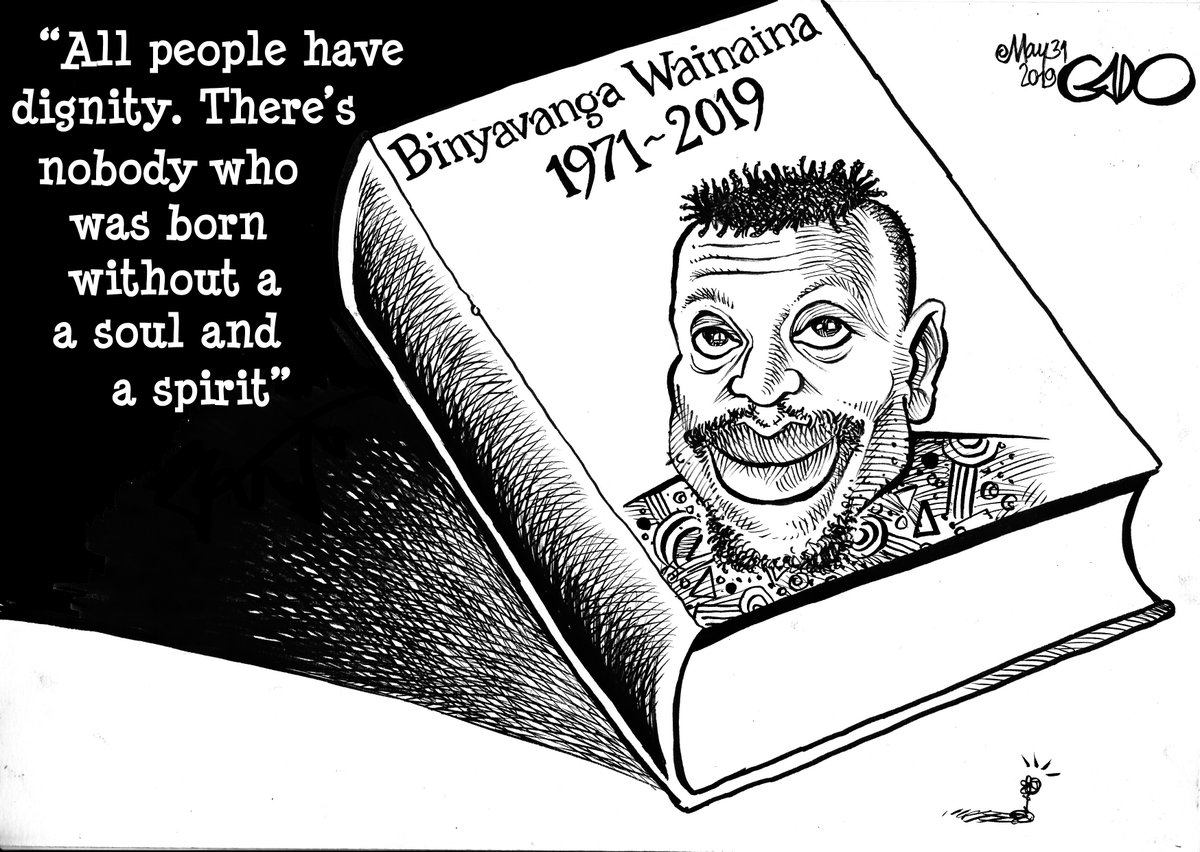

Personally, I didn’t know Kenneth Binyavanga Wainaina (a.k.a Binya) until the sad news about his passing broke. It was on a morning of the 22nd of May while I was attending the 11th annual Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere Intellectual Festival at the University of Dar es Salaam. I hope there will be a Binya’s Festival in the near future.

First, it was through a post of an extract from Binya’s famous essay “How to Write About Africa.” The truth is that I had never read any of Binya’s work till that day. The extract was simply great. I don’t have those fancy words to describe it. All I can I say is this: It moved me! I was awed with the power of imagination that went into that extract. I had not yet read the whole essay remember. There is this other thing they use a lot in literature… yes, satire!

Then, I started seeing condolences pouring. It was in one of those WhatsApp groups to which I am a member. And these were from people in the group that knew Binya or his work or both. My first reaction was how come so great a person with such great works ever existed without my knowing him? As if that were not enough, my next door neighbor – a Kenyan!

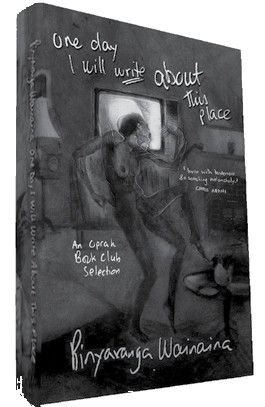

Frantically, I searched the internet to keep up with the pace. Boom! Here came the real thing: Kwani? I quickly made the connection. So, this was the genius behind Kwani? Ah!

I knew Kwani? But never its co-founder. I will introduce one person whom, I guess, was the link between me and Binya’s co-creation. This is none other than Yvonne Adhiambo Owour, another great Kenyan writer and winner of the 2003 Caine Prize for African Writing, just a year after Binya scooped the same.

Between 2009 and 2010, I had the honor of working alongside Yvonne and a handful of other great minds in an ambitious project. The Aga Khan University in Nairobi-Kenya was creating (from scratch) a Faculty of Arts and Sciences in East Africa, more or less like the one in Karachi, Pakistan. We were two broad teams; an academic planning team where I was attached and a facilities planning team. The academic planning team had sub-teams under it.

Yvonne was leading the Digital Expressive and Business Arts (DEBA) team. I was in the Material, Natural and Systems Sciences (MNSS). Well, to cut the long story short, our task was to design what would become an undergraduate degree programs for the university.

It was during this time that I got the feel of Kwani? Yvonne used to hold weekly sessions where its writers would come and share their works and writing experiences. The idea behind this, I think, was for the work we were doing at the university to get some inspiration from those who have been there and done it.

There were moments when I wondered what a geographer like me was doing with these literature enthusiasts. I don’t know whether it is because of the head of academic planning at that time who always insisted that we worked in sync so that each one knows what the other programs were doing. Or just that I had this deeply engrained appreciation for art, literature, and related genres but had increasingly lost touch with them after being tormented with No Longer at Ease, Mine Boy and The Great Ponds in secondary school.

Did I mention that it’s the rubber-stamp-look of Kwani? logo that has always amazed me. I wonder who designed it! The logo aside, the talents these young writers demonstrated was mind-blowing. Some had already published their works and I could tell, then, that it wasn’t piece of cake. I was just coming from my 6 years of university life but had never encountered literature or art professors leading similar initiatives.

That was Binya!

Not long after that I returned home to Tanzania to take up a teaching position at my Alma Mater, the University of Dar es Salaam. The encounter with with Kwani? is an experience I continued to cherish. Reading about how several people knew its cofounder in the wake of Binya’s untimely demise, one can’t deny the fact that he was a true generous genius.

He touched so many people’s lives in so many ways. What I have really come to admire about him, posthumously, is his daring attitude (if I may thus call it) that demystified literature and art as things of the university. He was, ironically, a typical nonconformist. I think Binya was one of very few people who fully demonstrated to us that you can go extremely contrary to the norms and traditions and still make a huge impact.

Some articles I have read about Binya in mainstream media in the region these two past weeks show how he battled with art and literature barons. Most of them have locked themselves in university departments of arts and literature, publishing houses and the like. Binya proved to us that literature and art is not the thing of the university and academics alone.

The truth of the matter is that, they – art and literature – have virtually died there – in the ivory towers. Literature departments in several universities in the region, for instance, are mere appendages of education departments just busy preparing literature teachers for secondary schools. Binya brought literature and art into the streets and created space for raw talent mostly those who had never set their feet in the hallowed university halls or any other formal higher learning institutions, for that matter. Nor in Alliance Française, British Council and Goethe Institut located within East Africa.

I am very sure this is how not to write about Binya. But, at least, I made my ignorance about this great child of Africa more precise. His legend will leave on, illuminating our intellectual paths and literary imaginations.

Rest In Power Binyavanga Wainaina!