Localizing (Local) Content in Agriculture or Locating One’s Name in It?

Dastan Kweka

Local content in extractive industries (oil and gas) seems to have become a buzzword less than a decade since Tanzania discovered significant quantities of natural gas. While there is work to do to improve regulation – and consultation – there is, also, a room to explore linkages with other sectors, especially agriculture. Nevertheless, assuming that local content is non-existent in other sectors (read agriculture), just because there is no sector-specific policy, amounts to starting off on the wrong foot.

The Natural Gas Policy (2013) defines local content as; “added value brought to Tanzanians through activities of the natural gas industry.” The policy adds, “These may be measured and undertaken through employment and training of local workforce; investments in developing supplies and services locally; and procuring supplies of services locally.”

Moreover, the Local Content Policy (2014) defines local content as:

“The added value brought to the country in the activities of the oil and gas industry in the United Republic of Tanzania through the participation and development of local Tanzanians and local businesses through national labour, technology, goods, services, capital and research capability.”

Although both definitions are relatively narrow – confined to oil/natural gas, the (natural gas) policy recognizes the importance of establishing linkages with ‘other strategic sectors’, such as agriculture – a sector that employs more than 67 percent of the population and accounts for one-third of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Other actors have, notably, recognized the importance of going beyond linkages. For instance, the Agricultural Council of Tanzania (ACCT) and Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Research Organization (STIPRO) – are already calling for a sector specific local-content policy. In advancing its agenda, the ACT position paper observes that:

“The development of local content policy in many countries has advanced mainly in the oil and gas sector, and less so in the agricultural sector. However, for Tanzania whose economy is heavily dependent on agriculture, and where the government is making deliberate attempts to attract foreign investment into the sector, it is important to have a local content policy that will ensure that foreign investment results in a broad-based agricultural growth. This is especially considering the fact that close to 80% of the population depends on agriculture for their livelihoods.”

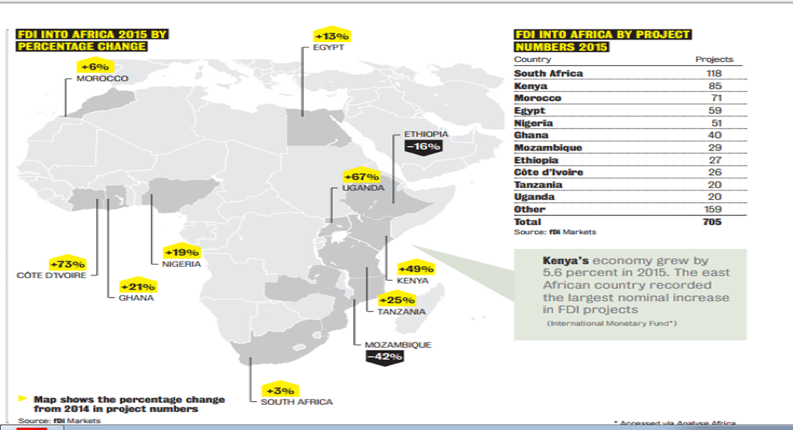

Indeed, Tanzania is making deliberate attempts to attract Foreign Directive Investments (FDIs) and has continued to performrelatively well. See the map below:

FDIs are, generally, built on the promise of (maximizing) local content benefits i.e. jobs, business opportunities, skills transfer and capacity building etc. Take the example of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) on jobs:

“The SAGCOT Investment Blueprint, states that the GoT [Government of Tanzania] seeks to attract US$2.1 billion of new agribusiness investment over the next 20 years in order to bring at least 350,000 additional hectares into commercial production incorporating Tanzanian smallholders into internationally competitive supply chains. Much of this will be expanded smallholder production. In the process, the SAGCOT Program aims to create at least 420,000 new jobs and lift more than 2 million people out of poverty.”

And in terms of technology transfer, SAGCOT’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Geoffrey Kirenga, notes:

“We observed with satisfaction, for example, that smallholder farmers are very receptive to new technologies. Our efforts to give them appropriate support have enabled potato, soya and dairy farmers to enjoy a significant increase in productivity.”

The promise of (cheap) labour – a basic form of local content – features constantly in SAGCOT presentations on opportunities for investors in the corridor, and the project’s blueprint is explicit on opportunities for suppliers. It is, therefore, surprising that SAGCOT’s Head of Policy, Neema Lugangira, who describes herself as a local content expert, is bragging about “initiating” local content in agriculture (or within the corridor). Can efforts to ensure there is a “robust local content in place”, as she claims, amount to initiation?

Corporate investment in agriculture is risky, and, smallholder farmers – often a weaker party in the Public Private Partnership (PPP) configuration, end up with fewer benefits (if any) than anticipated. The famous BioShape case in Kilwa district is a case in point. In light of this situation, we should ask the ‘champions’ and ‘initiators’, whose local content are you advocating? Maybe the answer is in SAGCOT’s 2016 report, especially a statement from the chairman of its Board, Salum Shamte, as excerpted below:

“Our investment in new opportunities broke ground on a significant expansion of investment by many of our partners. To mention a few, we are proud of Asas Dairies Unilever, YARA, Seed-Co, Syngenta, Mtanga Farms, Kilombero Plantation Ltd., and Silverlands. We have also seen increased investment by many of our SME partners such as Darsh Industries, Litenga Holdings, Rafael Group, Beula Seeds and many others. We are also very encouraged by the response of smallholder farmers. Many of them have demonstrated willingness to learn and work together. Associations and cooperatives are learning new ways to work efficiently and increase production and productivity.”

So, while new (business) ‘partners’ are investing or going for expansion, smallholder farmers are being taught ‘new ways of work’, as SAGCOT seeks to achieve “responsible commercialization of agriculture.”

It is important to highlight the issue of (and potential for improving) local content in agriculture. And if done well, names will be earned! But ignoring facts, and exaggerating one’s role, is not a better way to do it.