FROM THE AUTHOR OF ‘MABALA THE FARMER’ & ‘HAWA THE BUS DRIVER’:

I am so tired of innuendos and accusations against those of us who are arguing that:

a) English is key for all Tanzanians, not just a small class

b) The best way to teach English to the majority of Tanzanians is not to use it as a medium of instruction … a fact testified to not only by Tanzania and which has nothing to do with Tanzania’s learning skills

It has nothing to do with patriotism or romanticism or whatever other epithet is being thrown at us (I am reminded of a Tea Party Republican I met who accused Obama, without any evidence, of being both a Liberal and a Republican).

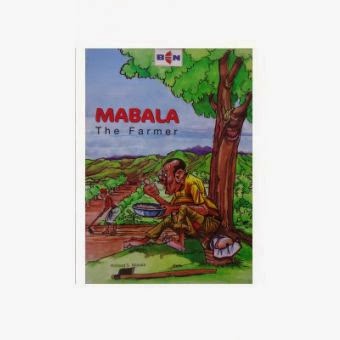

I am a teacher of English and I am proud of that. I taught English in different institutions for 20 years and I still continue to do so. I trained as a language teacher and I believe there are better methods of teaching English than just talking in English about any subject. When I first came to Tanzania, the claim was that every teacher is an English teacher which, even in 1973 was patently not true of some of the teachers I taught with (and Milambo SS was one of the top schools in the country at the time. And I am not referring only to Tanzanians. Even some of the expats who came were patently not English teachers either). Yet in those days, for example there were only 6 or 7 schools teaching Literature in English at A-Level and the number of people doing the O-Level exam was, I believe, less than 10,000. Mchujo ulikuwa mkali sana and the majority of those completing primary school still did not get a chance to show whether they could or could not use English as a medium of instruction.

Yet by 1978 the Presidential Commission on Education led by Jackson Makwetta, which was, I think, to date the most comprehensive review of education in Tanzania came to the conclusion that Swahili should be the medium of instruction not English. That was not their only conclusion and they looked at all aspects of the educational system but it was a key one. The British propaganda machine went into overdrive in response to this heretical conclusion (do I see shades of the same now?) and by hook or crook, I don’t know which, convinced/forced/induced the report to be changed. Part of the inducement was the introduction of an English Language Support Programme in which I have to declare conflict of interest ha ha ha. Since none of the books were written by Africans and certainly not by Tanzanians and contained such classics as ‘It Never Snows in London’ I decided I could at least write a book which talks about Tanzania. Hence the birth of ‘Hawa the Bus Driver’ and ‘Mabala the Farmer’. Some people actually criticised me for kuhalalisha the support programme which was not entirely honest (rumours were they dumped the books left over from a similar programme in, I think, Malaysia.

However, even that plan began to unravel Research carried out by their own people, Criper and Dodd, came to the conclusion in, I think, 1984, that the large majority of the then small number of secondary school students, did not have sufficient English to study in English. This was way before the rapid expansion of secondary education and, though I can’t remember exactly, I doubt whether the number of students doing Form Four reached 30,000. The first coordinator the British brought for the programme pronounced after a year or so that he was convinced that English as a medium of instruction was being used to prevent universal secondary education …. language as barrier not doorway to education. He was rapidly removed from his post.

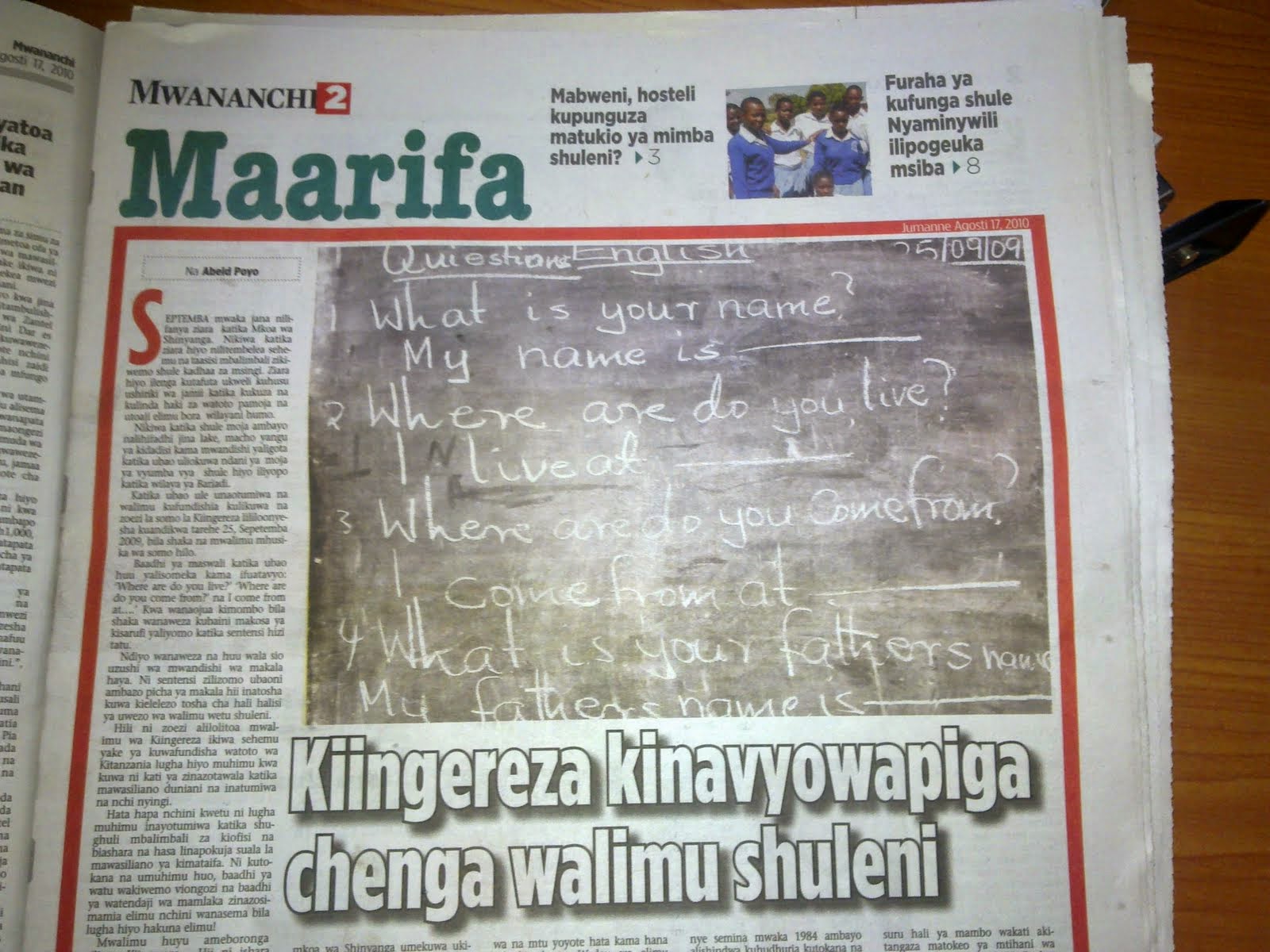

During that time (1973-1989), I was marking the National Exams for English and Literature in English. It was a mammoth job but unfortunately was made much easier by the number of schools where the students had no English at all so in order to keep up with our daily targets we could take a school and mark it in 10 minutes (with 2 different people marking every question). This was because not a single student in the school could write more than 5 lines, unless they copied part of the Comprehension passage). Ask anyone who marked the National Exams and they will tell you the same. It was a soul destroying exercise because you knew you were marking the school not the student and that they did not have the English to do exams in English. All this was before the rapid expansion of secondary schools that we have seen over the last 15 years.

In the meantime, researches continued to show that a decreasing number of students were able to study using English as a medium of instruction despite all the programmes thrown at the problem. I am not aware of any research that shows the opposite.

Therefore, as an English teacher and educationalist (yes I am) I fail to understand why academics and experts in other fields cannot understand that a child needs to study in a language they understand. I accept the argument about Kinyaturu etc and maybe that should be visited as well but I think it is being exaggerated. In my work in NGOs and for UNICEF I have travelled to most parts of the country, including remote villages, and there are not so many places where you cannot be understood if you talk in Swahili … not by everyone but by a large number. And the younger the group the more likely they are to understand you. This, I accept is a personal observation and should be backed up by research (although the Uwezo researchshows the large majority do understand Swahili) Why on earth do we want to repeat the definition of madness by continuing to preach the same things over and over again when to date the situation continues to go downhill whatever remedies are tried. This belief that somewhere over the horizon suddenly all will be light and peace and people will be able to actually understand what they are being taught has no basis in fact.

That is what I fail to understand. Of course the academics and experts in other fields do belong to the educational elite, and to a certain class which might be a part explanation of the situation but I request that they go and try to teach their subjects, in English to the mushrooming secondary schools for at least six months and then come back and continue the debate. I gave the example of when I was teaching in Kibosho Girls 1982-5 to members of the elite (a high class school) but which had a quota of girls from Kibosho itself. When I was teaching history, it was certainly good for my creativity as I had to invent all sorts of new ways to get them to understand, including drama etc and whenever I got to a historical concept I would teach in Swahili and then repeat three times in English before moving on. What a waste of time for someone who wants to teach History, or Physics, or whatever subject they would like their students to understand. If I had taught in the language they understood, they would have needed less classes in History in order to understand more (the primary history syllabus in Swahili was actually more detailed than the secondary school one) and more classes could have been given to the teaching of English in a systematic manner, using the best methodologies available to ensure that their English improved as well. I am 100% sure the students would have had better English as a result.

So we should also not divert the discussion by saying that there is no point in repairing the doorway as the walls are also very weak. We should both install a new door i.e. access to education and address all the other issues as well. But let’s stop throwing unfounded accusations against those who have taught English and have done the research and argue academically on the matter. We should not be led by our assumptions.

The issue of English language in Tanzania’s schools remains a big problem that requires serious efforts to address it an not take it as joke.

I need the analysis of mabala the farmer