A Review of:

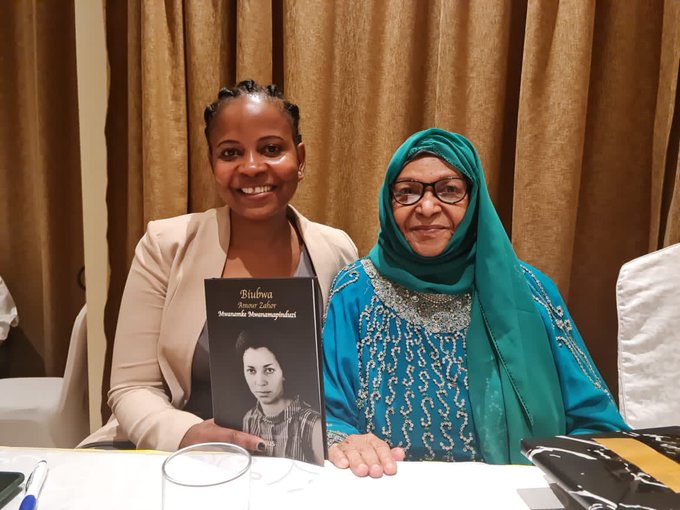

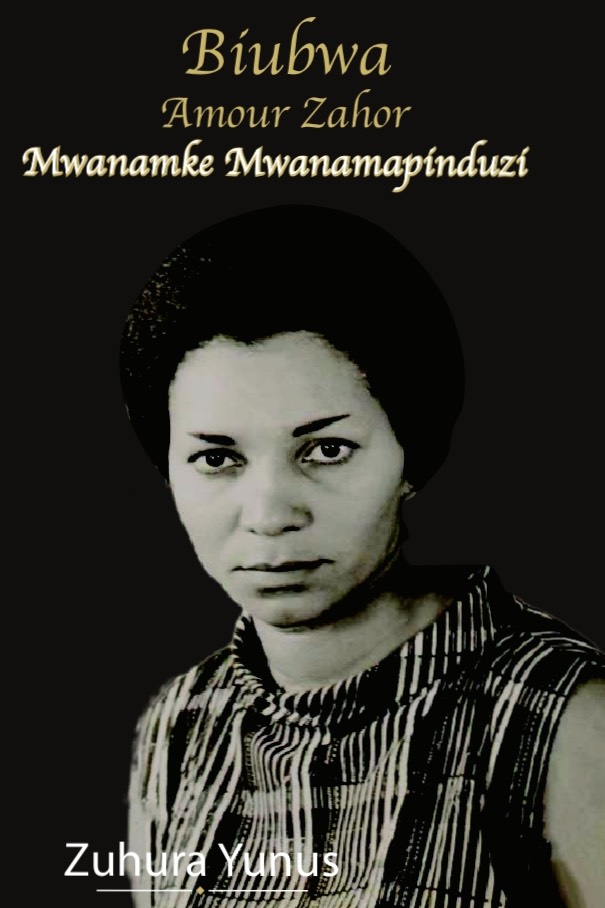

Zuhura Yunus (2021). Biubwa Amour Zahor: Mwanamke Mwanamapinduzi. E & D Vision Publishing: Dar-es-Salaam.

Biubwa Amour Zahor is an unsung hero. Unsung because many of us did not know her before the publication of this brief, yet sharp, detailed, and powerful biography. She is a heroine in many fronts. Biubwa is not only a political hero, but also a political feminist hero.

By a broad definition, feminism is about challenging the status quo and power dynamics in a society that undermines social justice. Political feminism underscores that there is no political, social, and economic justice without gender justice. Many “feminists” speak of these ideals, but Biubwa acted and lived them. When she was still a teenager, she went against the existing discriminatory society and her own family’s gendered norms. She dated a white man, then later on married a black man. In that, Biubwa was frameless i.e., she did not accept to be framed or put in a racialized society’s box.

To be a political feminist, the life of Biubwa illustrates, is to be frameless.

In the book, her biographer, Zuhura, explains how strangely bold it was for Biubwa to marry outside her ‘race’. In the 1950s, generally the Zanzibari society did not allow black African men to marry Arab ladies. Pertinent to our time, Biubwa continued with mainstream schooling even after she delivered a baby. A progressive act, which is still debatable in the contemporary Tanzanian society – whereby the national education policy does not yet give pregnant girls an explicit access to public education. It is probably the path that was established by bold women, such as Biubwa, that Zanzibar’s education policy is fairer when it comes to access to education for pregnant girls as compared to mainland Tanzania.

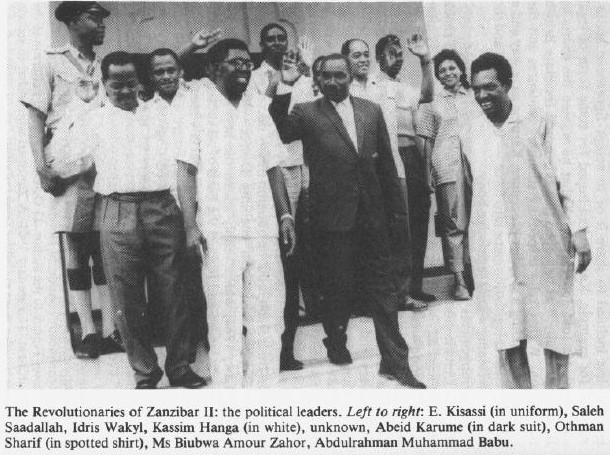

Biubwa was at the center of 1964 revolution in Zanzibar. She quickly read the times and acted ahead of time. She was in the action. Being a single mother with five children (and later on eight children in total) by the time of the revolution did not stop her from almost a full-time involvement in post-revolution political activities. Nothing could hold Biubwa back – neither men (her husbands and partners) nor family.

Cue to being frameless, she hanged out with powerful men, not for the sake of hanging out, but to influence and bring about political change. Without sidelining other women (she was friends, and could even live, with the wives of the men she worked with in politics), Biubwa became an integral and useful political operative in establishing and consolidating the post-revolution state. She carried out covert operations even outside the country.

Being frameless is almost synonymous to being controversial. Biubwa’s life was full of controversies. In that, many questions remain that need answers in regard to her life and the political context she has lived in. In the biography, Zuhura has attempted to situate Biubwa’s life in the social and political contexts that she was socialized into.

The author gives an account of the revolution and the history of Zanzibar in the last half of the 20th Century. In juxtaposing the book with existing literature on the revolution and the history of Zanzibar, there is a significant amount of triangulation. However, Zuhura brings forth critical observations that conventional literature on the Zanzibar question does not explicitly show. For example, the role of women and, in particular, Biubwa as well as other critical players, such a Brigadier Absolom Amoi alias Ingen.

This book is extremely political. Reading through critical eyes with reflections on the current state of Tanzania – one can identify where we have progressed and where we have regressed. For example, there is progress in justice structures, such as presence of courts and open inter-marriages. We have regressed in many fronts, such as setting up trumped charges for political opponents, having similar prison conditions as to those of the 1960s as well as forgetting to fully honor the role of women in political engagement.

The style of the biography is smooth. It starts as a simple descriptive narrative yet, as one turns to each new page, the book becomes analytical with a deep and powerful message in between sentences. Carefully, Zuhura pushes for a strong political statement without any agitation. This could be the hidden skill of the author who is an international journalist.

Although written by a journalist, the book is not simply journalistic. It is analytical. It has an argument.

Yet I wonder why the book is more or less mute about the role of the revolution in the union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar. I think the author could have provided more context, in particular the historical evolution of Zanzibari politics following the union. I almost felt that the book is silent on the controversial union question.

There is a glimpse of that with the scene of Biubwa’s trip to China, prospected studies in Russia and more so her work in Tanzanian missions in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. But I would have loved to gain more insights as to how Biubwa performed in dealing with new set of powerful political men from the mainland Tanzania who were now part and parcel of Zanzibari politics. Some akin to the way the book has engaged with her encounters with Ambassador Paul Rupia.

The sweet thing about the book is the perfect use of Swahili. It introduces a wider set of vocabulary, especially from Zanzibar. To be nice to readers, Zuhura has put an index to define those new or rather not so popular used words in day-to-day Swahili in mainland Tanzania. The book is thus a contribution to the Swahili language and writing.

Nevertheless, since Biubwa’s story resonate with the global thirst for appreciating powerful women in liberation movements, the book will be of great contribution to the literature if there could be an English translation. Moreover, it calls for further research as it opens the eyes and provides a hint that there is more than we know about the Zanzibar revolution.

Biubwa is an unsung heroine – not only in political liberation movements, but feminist theory.

Thanks for this insight. Well articulated.

Thanks for this opportunity to know her, congratulations to her to be part of our nation future

Love her, keep letting us to know more women whom were there bullied our nation.

Beautifully written, insightful. Thanks

Thank you for reviewing the book, I can’t wait to read it!

Thanks I did not know this mama history always writes about man only were I Zanzibar Revolution

Some birds are not meant to be caged, that’s all. Their feathers are too bright, their songs too sweet and wild. So you let them go, or when you open the cage to feed them they somehow fly out past you. And the part of you that knows it was wrong to imprison them in the first place rejoices, but still, the place where you live is that much more drab and empty for their departure.” Stephen King, Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption.

I have read Biubwa’s Biography, I concluded that she is a “a bird that was not meant to be caged”. I have never met her but I felt for her trials and tribulations.