By Sabatho Nyamsenda

On Challenging Results

Once declared, the results of presidential elections cannot be challenged in court. This is a feature of the present constitution, which was inherited from the one party era. Nyerere, the founding father of Tanzania, once said that the constitution gave him enough power to become a dictator if he wanted. This should show us that the problem is historical and systemic rather than simply the misrule of an individual. In which case, the solution should also be systemic.

I must add that, as a pillar of democracy, an electoral process is supposed to be a sovereign process. It’s through their participation in elections that the people decide which leaders and which type of policies should govern their country. This means that, if there are any flaws in the process, then the solution has to be internal and should come from the people themselves.

On External Interventions

Democracy cannot be imposed from without. In the US, the opposition party – the Democratic Party – alleged that the 2016 electoral process was manipulated by the Russian government. The elected US president, as we know, lost the popular vote. I heard no one inviting the international community to intervene in the US to restore democracy. The US police force has been committing genocide on black Americans yet there are no calls for external intervention in the US.

Even though we do not openly acknowledge it, the international community is a code word for Western governments and agencies. It’s the West that uses its military and economic clout to intervene in other countries. The West also dominates all global institutions, from the UN Security Council to the IMF and World Bank. Now, the relationship between the West and Africa from the late 15th century to the present has been characterized by oppression, genocide, plunder, exploitation and dehumanization.

Two decades ago, the US told the entire world that it was going to Iraq to bring about democracy. What happened? Genocide, physical destruction destabilization and plunder of oil. A decade ago, NATO invaded Libya, an African country, with the same excuses. What happened? Libya, once the most stable and prosperous nation in Africa, was turned into a failed state, with civil wars, terrorism, neo-slavery, plunder of resources as the order of the day. Che Guevara warned us against trusting imperialism. “Not even by an iota,” he warned. So, to cut the long story short, the West should stay away from Tanzania and let Tanzanians themselves decide their future.

On Human Rights

As an academic, I am interested in getting the question right. For, if we do not have a proper diagnosis, how will we able to find the right cure? So, let me start with the problem of the Human Rights industry (by this I refer to all organizations that take human rights and the rule of law as the point of departure). The basic approach used by the Human Rights industry to political problems has been naming and shaming. They go to a country, identify an individual or groups of individuals who are said to perpetrators of human rights violation and call for their trial.

Since African governments are deemed incapable of enforcing the rule of law, then international actors are always invited to take actions. All sorts of actions from travel bans to economic sanctions and military invasion are used, and consequently end up aggravating the situation and creating more problems instead resolving them. In the end, these international actors take no responsibility for their actions but reproduce the same framework elsewhere.

On Zanzibar’s Politics

Most of African political problems have their historical roots in the colonial era, and their solution requires the involvement of all actors, as survivors, and not simply punishing the so-called perpetrators. Zanzibar could be the case in point. The political division in Zanzibar has its root in the colonial division of Zanzibaris into races and tribes and the politicization of these differences. The British colonialists masterminded electoral rigging in Zanzibar to ensure that they hand over power to a party that they thought belonged to a ‘superior race’ and would maintain neocolonial ties with them. As a result, a black nationalist party which felt disenfranchised toppled what it saw as an Arab regime which took over the reigns from the British. These racial and ethnic differences were then politicized and resulted in the marginalization and oppression of one part of Zanzibar.

After years of alleged electoral fraud and violence, the leading politicians in Zanzibar reached a political consensus to establish a government of national unity in 2010. The 2010 elections were the only peaceful elections in which all parties accepted the results. I still think the future of Zanzibar lies in dialogue and resumption of the government of national unity. The winner-takes-all elections do not work in Zanzibar.

On Pre-Magufuli’s Tanzania

As for Mainland Tanzania, I am actually astounded by the praises given to pre-Magufuli’s Tanzania, as if the problems we have surfaced from nowhere 5 years ago. It’s true that Mainland Tanzania built a strong reputation due to its devotion to the liberation of Africa and the oppressed wherever they were. Mainland Tanzania were the headquarters of the liberation movements in Southern Africa and Tanzania played an active role in the struggle against imperialism in all its forms. Nyerere was one of the leading advocates of the New International Economic Order, a campaign by countries of the Global South to redress the power imbalances and economic dispossession within the global capitalist system. Domestically, Tanzania pursued egalitarian economic policies under the policy of socialism and self-reliance.

As expected, Tanzania’s position was antagonistic to the interests of imperialist countries and this soured diplomatic relations with the West from time to time. After Reagan and Thatcher came to power in the US and UK respectively, the duo specifically targeted Tanzania, cutting assistance and directed the IMF and World Bank to do the same, as a way of bringing Nyerere’s policies down. Nyerere voluntarily relinquished power in 1985. His successors implemented directives by Western governments and did away with all the positive legacy of the Nyerere era.

The one thing that the post-Nyerere regimes did not do away with was the colonial state that Nyerere – like all other African nationalists – inherited from the colonial masters. This powerful machinery, with its oppressive laws and coercive devices, was established by the colonial masters to suppress Africans into submission to colonial plunder and exploitation. On the morrow of independence, it was manned by black Africans for precisely the same purpose.

Neoliberal reforms pursued in the 1980’s and 1990’s recharged the inherited colonial state and made it stronger internally but very weak externally. That is to say, the neoliberal state became very coercive in its relations to its own people but very weak when dealing with Western corporations and governments. The hidden slogan of the neoliberal state is: “Against the People, For Corporations.” This has happened across Africa despite the re-introduction of multiparty politics and the ascendancy of human rights rhetoric.

With the crisis of neoliberal capitalism in 2008, the neoliberal order, with all its political paraphernaria, lost legitimacy. That is why, across the globe, there is a resurgence of populism – whether leftwing as in Sanders, Melenchon and Corbyn or rightwing as in Brexit, Trump, Modi and Bolsonaro.

On Magufuli’s Tanzania

This foregoing background is important when analysing Magufuli’s statecraft and economic reforms. Like any other African leader, he found the powerful machinery from colonial era intact and ready to implement what he wishes. He used it for various purposes – some progressive and others regressive. The progressive ones include bringing the state back in the economy as the leading owner of strategic enterprises like airways, marine and railway transport, power production; reclaiming Tanzania’s permanent sovereignty over natural wealth and resources; rejecting some free trade pacts, and providing free primary and secondary school education. In doing this, he has invited the ire of multinational corporations and Western governments, which still cling to the already discredited free market mantra that state should stay away from the economy, and let the market (read: corporations) decide.

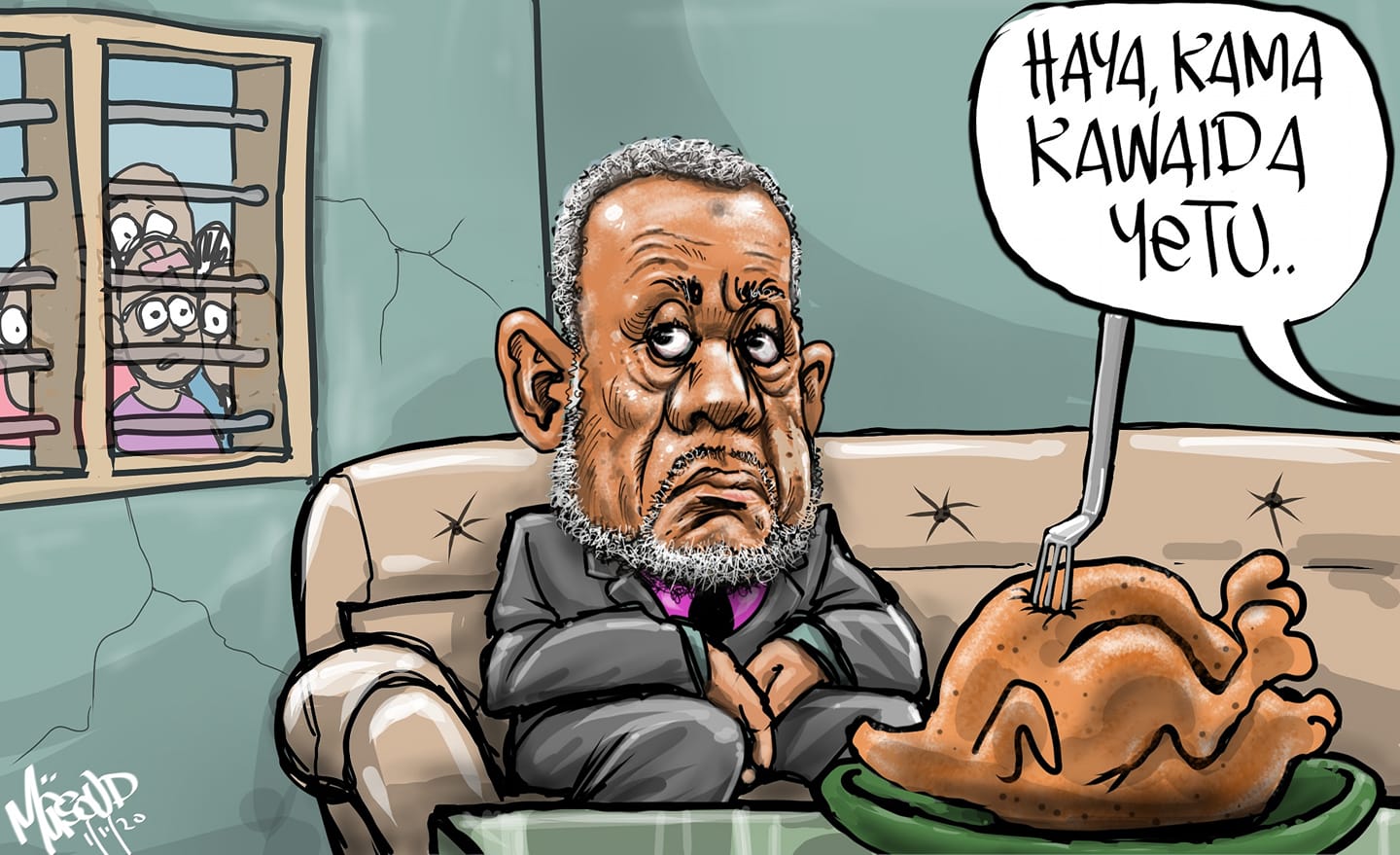

The regressive intervention under Magufuli includes the extreme use of the state in quashing political dissent. In this latter role, the Magufuli regime has been extreme but by no way exceptional. The West and the corporate-funded Human Rights industry has used this weakness as a cover to push the country back to full swing neoliberalism. In the “Dinosaur of Dodoma” – as the Economist referred to Magufuli – the West has found an indefensible black person at whom to throw their racist slurs about Africans. The myth of Tanzania’s democratic past will remain what it is: a fairy tale.

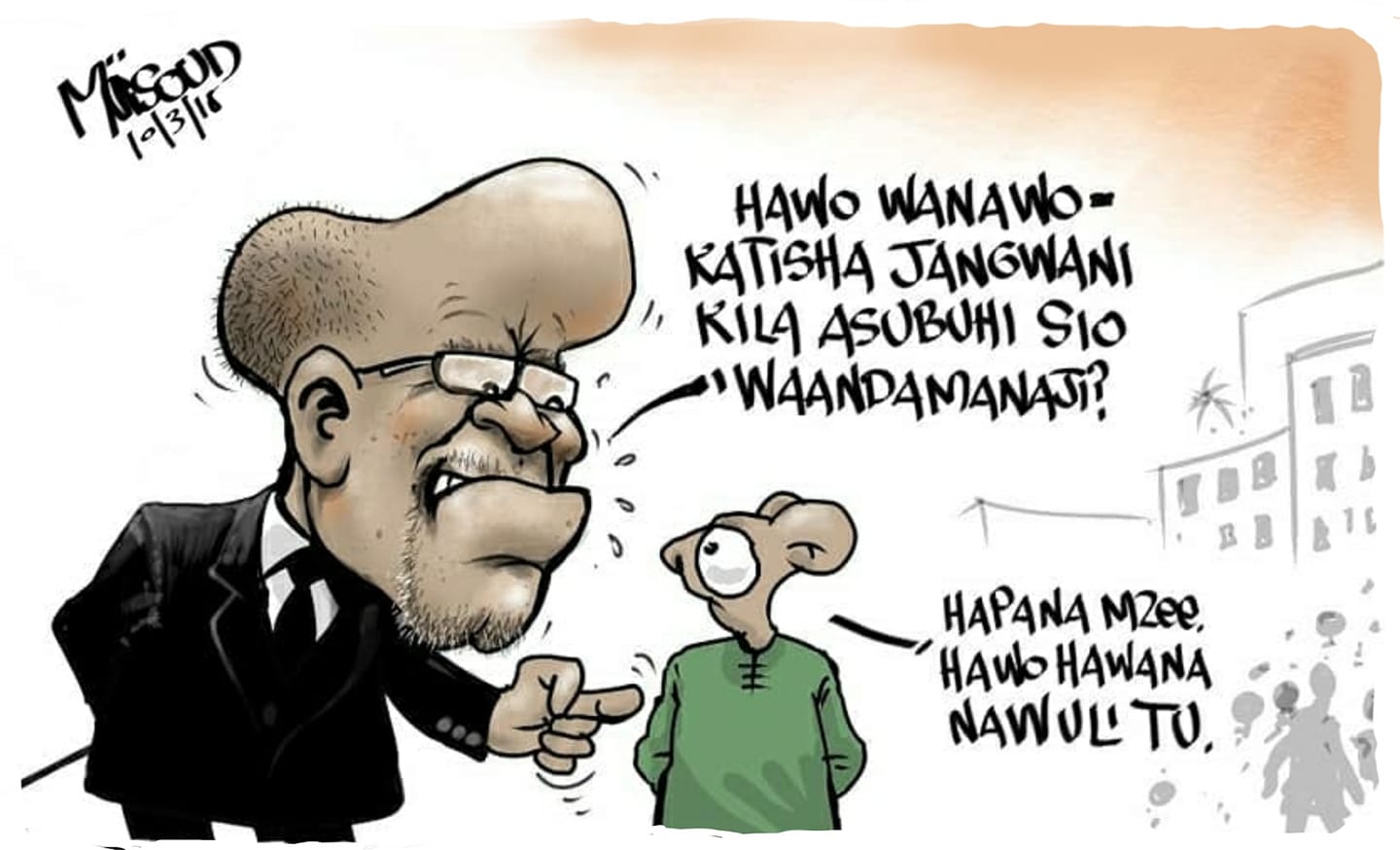

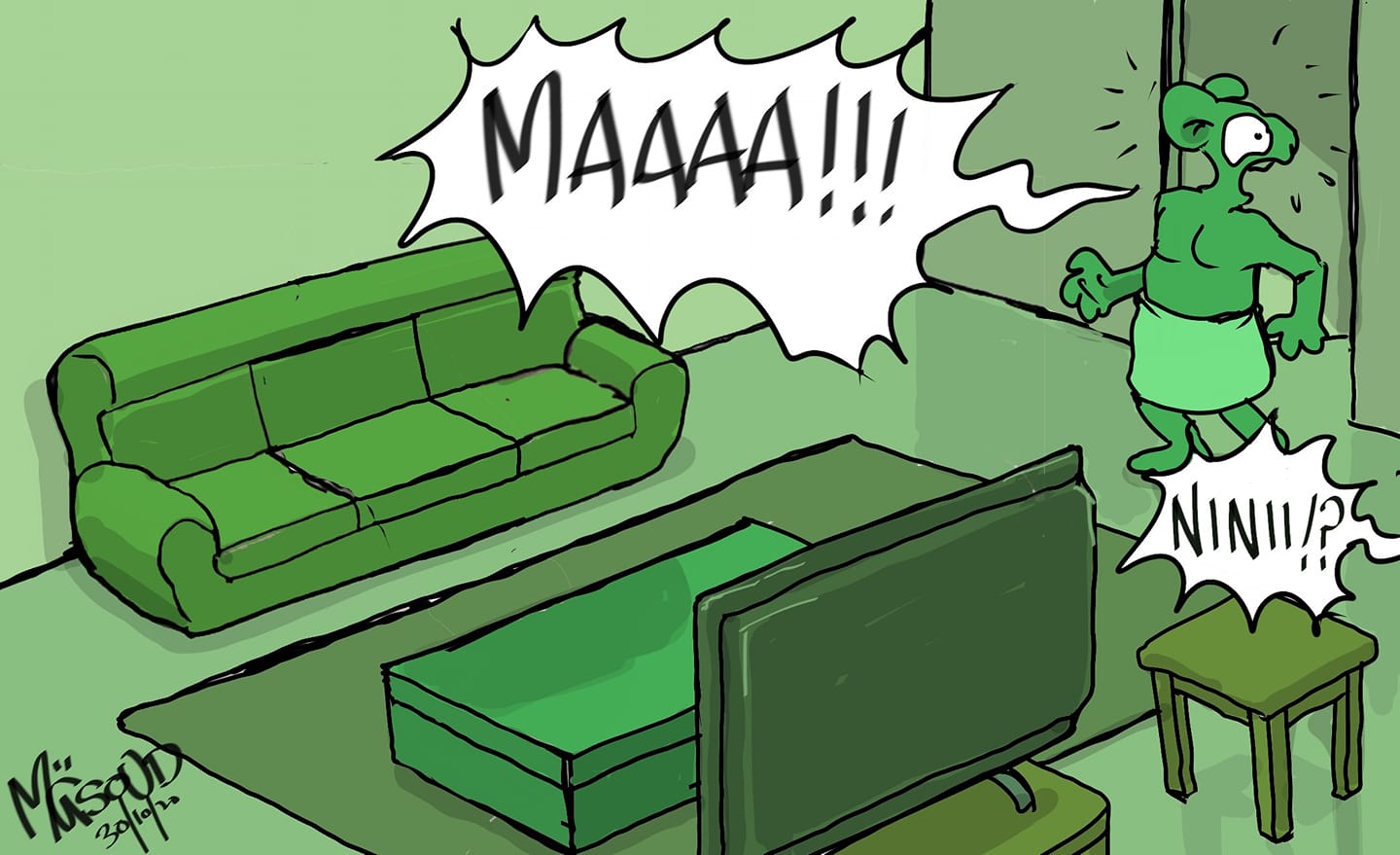

Which democratic past is being alluded to? Is it the Nyerere era with its forceful villagisation, the single party politics and detention without trial? Or the post-Nyerere era where the majority of Tanzanians were left to languish in the jungle called the free market where powerful corporations pounce on those who labour and where the all powerful state deploy armed forces to evict smallholder producers and street vendors to make way for large-scale companies?

On Post-Magufuli’s Tanzania

That is why I am saying that Tanzanians should be left to decide how to get out of the current stalemate. More than ever, a national dialogue involving all actors – not just politicians – is needed. From my links with different grassroots organizations across the country, I am sure that the majority of Tanzanians will use the national dialogue to push for reforms that would aim at radically transforming the state to put more power in their hands. They would push for a popular state, like one in Bolivia under Evo Morales or Venezuela under Hugo Chavez, that promotes multiparty democracy but goes beyond to institute popular forms of power, oppose imperialism and implement welfare policies. That type of state is inimical to the neoliberal state promoted by the US governments, free market fundamentalists, and human rights crusaders.

Well done comrade! I always say; the problem with we African is failure to deal with the core problems from the roots rather we jump to eradicate the outcomes which is a very wrong approach.