The Blue Economy Agenda: New Dawn for Africa or just another resource grab scheme?

By

Ronald B. Ndesanjo

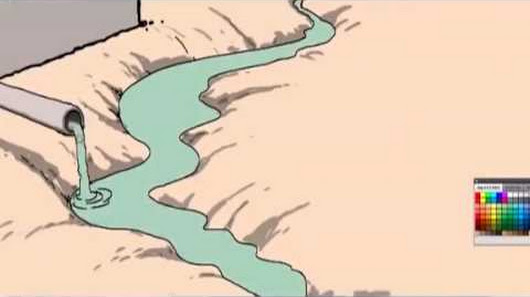

The World Bank defines the blue economy as sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, livelihoods improvement, jobs creation, and ecosystems sustainability. In simple terms, it entails the use of ocean resources for sustainable economic growth. This is what we have understood as blue economy until a week ago when the concept presumably got a whole new meaning to include inland water resources. Lakes and rivers were added to the economic equation.

This redefinition was presented during the Sustainable Blue Economy Conference held in Nairobi, Kenya between the 26th and 28th of November 2018. It was a meeting that touched on many things. But, more importantly, it was for mobilizing the global community to exploit the potential for economic growth, jobs creation, and poverty eradication that our blue resources offer.

Economic exploitation of our ocean (and indeed inland waters) resources is not a new thing at all. It dates back to antiquity. Therefore, the main question is: Why such heightened interest in blue resources now?

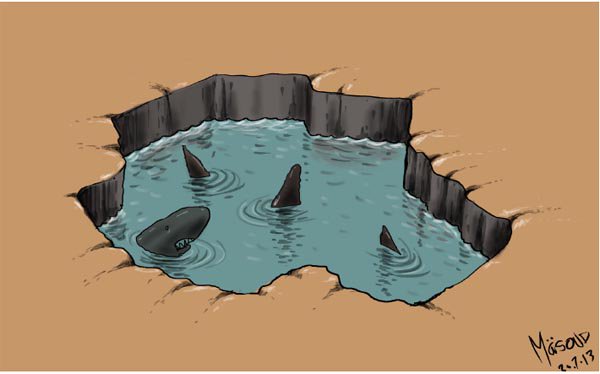

The overall aim for the Blue Economy, as far as its propagators are concerned, is twofold: to harness economic potentials offered by oceans (and inland waters); and to restore the health of our blue resources and the ecological systems they support. I am tempted to regard the former as the real motive behind the current Blue Economy agenda. As for the latter, I see it as a mere campaign to legitimize the underlying economic motives.

We have seen this strategy working in other resource exploitation regimes. Be it forestry, wildlife, mineral ores, oil and gas – you name it. The key issue has always been whether there are tangible benefits to our local economies and small holders’ livelihoods. Let me share my reflections on this.

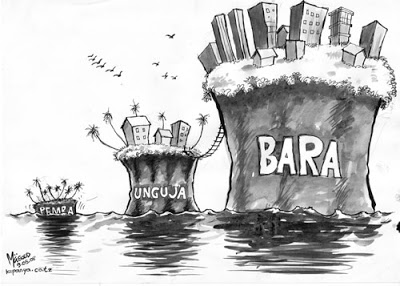

It is quite evident that there are very strong geopolitical motives behind the Blue Economy agenda, especially in the West Indian Ocean (WIO) region. The region is constituted by ten countries, namely Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, and France. The region is valued at US$20.8 billion annually in “Gross Marine Product”. In contrast, the global ocean economy is valued at around US$2.5 trillion.

Hence, by comparison, the WIO economy seems small. But is quite significant given the economic situation characterizing its countries. This potential is likely to be scooped by global superpowers.

The European Union (EU) has already entered into a partnership with Morocco, Mauritius, Senegal, and Seychelles to reform the countries’ fisheries. As if that is not enough, the EU’s target is to form coalitions on Blue Economy sub-sectors with at least 50 African countries. The EU, as a region, boasts 640 million euros of revenue and 3.5 million jobs in the Blue Economy and, from the look of things, the big boys want more cut in the sector. In doing so, where else to go than the West Indian Ocean region?

Interestingly, Seychelles was named, in the Nairobi meeting, as the floater of the first Sovereign Blue Bond; a 15 million dollar bond aimed at sustainable fishing and marine resources conservation. The money is coming from American investors with guarantees from the World Bank and the Global Environmental Facility. And this means business, big business. The big question is: what is in it for African countries in the region?

As I hinted above, the tone set in the Nairobi meeting made it very clear that even inland Blue Economy resources (Lakes and Rivers) are on the menu. This is where the potential locked in the Great Lakes regions come into the scene. One can’t help thinking of confirmed and potential oil and gas reserves beneath the Eastern Africa Rift Valley Lakes.

It has already been confirmed, for instance, that there are commercially exploitable oil and gas deposits in Lakes Turkana and Albert in Kenya and Uganda, respectively. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA)estimated (in 2013) that oil and gas reserves, respectively, amounting to 1.554 Billion barrels and 623.55 Billion cubic feet in the four East African countries of Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. An Activity Map from the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) indicates that virtually all the major water bodies in the country are under exploration. Mozambique also has enormous potential for gas.

Thus, when one hears of promises of financial and technological support in sustainable exploitation and conservation of inland Blue Resources, it is not very difficult to tell what the real motives are. This is only oil and gas. Much can still be said about fisheries, tourism, and aquaculture potentials in the great lakes.

Now let us look at how this Blue Economy thing fits into the current East African situation. The first thing that comes to mind is the local (riparian) communities’ welfare. Lake Victoria’s Basin, for instance, constitutes about 30 million inhabitants. About 70 percent of them are smallholders engaged in fishing, farming, and livestock husbandry. Equally important, the Lake serves as a source of food, energy, fresh water, shelter, transport, and environmental sink. Its fisheries are valued at US$800 pa. But, even in current standards, distribution of benefits (only from fisheries) is deemed inequitable with smallholders at the losing side.

Apart from potential investments in formalizing (economically) and protecting (for strategic reasons) Blue Economy resources, it still is quite vague how our local communities’ welfare will be safeguarded. There is no clear agenda yet on how local communities’ rights (access, ownership) to such resources will be protected especially after the big boys gain a foothold in the region’s Blue Economy sector. All I see now is what I dare call “blue PR” deceptively used to make an impression that global Multinational Corporations (MNCs) and their frontline institutions’ aims are socio-economically and ecologically friendly.

Yes, the big boys will help us in regulating fishing, pollution control through the transfer of modern cleaner technologies, curbing regional insecurity, climate change mitigation, etc. But for whose interest really? Ours or theirs? Or both?

The bigger question we need to ponder about is how to protect our people and their economies from potentially negative effects following the influx of new, bigger and powerful players in the Blue Economy sector with new rules of engagement likely to see smallholders being pushed out of the equation. I am very optimistic about the benefits we stand to gain from the Blue Economy resource exploitation. But, we need to put our house in order and very fast so as to better position our people and our local economies as winners.

Re-aligning legal and institutional frameworks should be a top priority to regional bodies like the African Union (AU) and the East African Community (EAC). The AU’s Agenda 2063, for instance, is a potential platform for Africa to position itself strategically to win big from her Blue Resources. Aspiration number 6 of the agenda is quite pertinent here. It seeks to attain people-centered development by tapping the potential of African youths and women who are drivers of the economy. Some flagship projects of the agenda, such as as the African Commodity Strategy and Continental Financial Institutions, could be re-aligned to ensure our people benefit equally from the Blue Economy.

At the East African level, regional institutions like the Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) and Lake Victoria Fisheries Office (LVFO) are better positioned to play a pivotal role in brokering for local communities’ interests. This goes alongside ironing out all problems, especially economic barriers (e.g. trade wars between Kenya and Tanzania) and streamlining transboundary natural (water) resource management mechanisms (ref. dispute over Lake Victoria’s Migingo Island between Kenya and Uganda). It is until this and many more are done when we, as a region, can confidently say that we are ready to do business or this Blue Economy epiphany will be just another resource grab scheme.