UK-based, Zanzibar-born Abdulrazak Gurnah has made us proud. Most importantly he has made us think. In Tanzania, Gurnah’s Nobel Prize win has indeed sparked both joy and debate.

Besides celebrating his achievements, debates around his identity have provoked discussions on issues related to dual citizenship and unresolved controversies about the Union (Tanganyika + Zanzibar) and the Revolution (Zanzibar’s). I do not intend to engage in such discussions. My interest here is the man himself, the writer, and his work in relation to what I raise here about cultural appropriation.

Gurnah has just joined Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka as the only two non-white writers from Africa ever to win the world’s most prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature. He is one of the most prominent postcolonial writers of his generation. He speaks out clearly against prejudice and racism. Announcing the Prize, the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, stated that he is awarded for:

… his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.

That is the reason why the world is celebrating Gurnah’s work. He has constantly posed questions around ideas of belonging, colonialism, displacement, memory, and migration in the world that is becoming increasingly hostile to ‘the Other.’ This shows how necessary a lively and broad-based discussion of our colonial heritage continues to be.

The colonial legacies and designs militate against the minorities and their lifeworld in the most patronizing way. To this, now, I turn to those I call the Fake Maasai – celebrities (musicians, athletes, authors, entrepreneurs, and others) who appropriate elements of the Maa culture to advance their careers. But they do not use their privileges to give voice to the historically marginalized Maa people.

Nasibu Mollel Lengai Ole Sabaya

“Kutana na Naseeb Nyange, Mtanzania wa kwanza kwenda kuchunga ng’ombe Los Angeles, Marekani” (Meet Naseeb Nyange, the first Tanzanian to go herding cattle in Los Angeles, US) read a text inscribed in Diamond’s image circulated on social media. On June 27th, 2021, the Bongo Flava star Naseeb Abdul Juma, a.k.a Diamond Platnumz, showed up for the BET Awards’ red-carpet donned in a red-gridded Maasai attire. His nomination stirred an intense debate on Tanzania’s social media platforms.

More than 20,000 people signed an online petition that sought to disqualify him from the BET Best International Act award on the grounds that he supported an autocratic rule of the late President, John Pombe Magufuli. Several Tanzanians, including fellow musicians, politicians, and activists, admitted to siding with Nigeria’s Burna Boy on the voting day. In contrast, Burna Boy actively participated in ENDSARS movement – Nigeria’s protests against police brutality by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). This one case suggests that celebrities do have or at least expected to have some ethical responsibilities. That they ought to be sensitive to their political or brand endorsement.

As part of the broader Tanzanian society, the Maasai whose culture (attire & beads) was being displayed expressed their opinion using humour as a tool of agency. At first glance, they laughed that the knife (sime) was not positioned properly and that the dressing style appeared somehow feminine (we are keen and curious observers). They also asked themselves which clan could fit him [Diamond] best.

However, at the second glance, and in relation to the wider national debate alluded to above, the Maasai protested that the Bongo Flava star never expressed any solidarity with them in their continuous struggle for land rights and cultural integrity. They were outraged by the musician’s performative appearance as Ol’mur̃ani (Morani) yet (purposefully) ignorant of the imposed hardships that the people he supposedly appears to associate with are facing in their everyday lives.

The Maasai youth and others sarcastically renamed him Nasibu Mollel Lengai Ole Sabaya. This wordplay of the name is quite telling because the one Lengai Ole Sabaya (former District Commissioner for Hai) is facing a court case for abuse of power during his tenure. Simply put, Sabaya is accused to have failed to use his privilege for betterment of the community. Some politically active Maasai youth took the matter seriously even by trying to seek audience with the musician to present their concern. The then failed plan was meant to request the Bongo Flava star to use his popularity to speak against injustices visited upon the Maasai people in Ngorongoro, Loliondo, Lake Natron Basin and other parts of the country.

Maasai in Tokyo

About a month after a Maasai in Diamond appeared at the Microsoft Theatre in Los Angeles, ‘Maasais’ once again attracted the world’s best Niko cameras, this time in Tokyo. On July 23, 2021, the 2020 Summer Olympics were finally officiated at the Olympic Stadium in Tokyo, Japan after a one-year pandemic delay. The most anticipated part of any Olympic ceremony is the Parade of Nations when athletes from each competing country enter the stadium together, marching under their national flag. Though the opening event was less attended due to COVID-19 precautions, familiar elements such as flag-waving, fireworks, musical performances, and cultural celebrations set the stage for the games.

Kenyan athletes stole the show as they entered the stadium with colourful Maasai regalia. Many viewers were thrilled and Kenyans expressed their excitement and sense of pride on social media platforms. I had mixed feelings.

On the one hand, I felt a sense of pride because my culture was being represented on the global stage. The country I love and partly considers home (yes, I’m conscious about the border thing, of course) is representing us -the East Africans. On the other hand, I had a sense of loss. I felt disappointed and cheated because I knew everything was performance marketing.

I am, by no means, saying that non-Maasai ought not to represent us at all. What I find disturbing is the trend by non-Maasai to cheapen and commercialize or trivialize the ancient heritage of our culture. Cultural elements that have deep meaning to our culture are often reduced by celebrities, fashion designers, and tourism entrepreneurs to exotic fashion. “The Olympics is the world’s biggest fashion show and we as Kenyans are winners, so I was combining the global print on a global stage with global winners,” said Wanja Ngare, the designer of the Maasai-inspired attire that Team Kenya wore at Tokyo Olympics opening ceremony.

Our culture is often despised unless a commercial value is attached to it. For instance, in the late 1960s, the Tanzanian state carried out what it dubbed “Operation Dress-Up” to induce the Maasai to abandon their traditional dress. As I have noted elsewhere, earlier on, a US-based news magazine run a headline, “Dressing Up the Masai”!

Like Tanzania’s Diamond Platnumz, Kenyan athletes and fashion designers are far detached from the Maa realities in the country i.e., their prolonged struggles over disparate notions of livelihood, territory, and wellbeing. Let us consider Laikipia – a place the Maasai are still fighting to call it home. The Kenyan neo-colonial state that celebrates the Maasai culture for its role in marketing the country in international fora (Olympics) and the multi-billion safari tourism, has recently threatened to send in military commanders to ‘kuwanyorosha’ (squarely chastise) those mobilizing to reclaim lost lands in Laikipia.

In his thesis, Green grabbing and the contested nature of belonging in Laikipia, political ecologist Brock Bersaglio eloquently argue that global demand to protect endangered wildlife at any cost has corresponded to increasingly more large-scale land acquisitions being carried out for conservation purposes. The first wave of land alienation and enclosures under the mighty hand of British colonialism (1883-1963) transformed Laikipia from a pastoralist rangeland into white highland. Under the quintessential neo-colonial Kenyan state, political elites, some of them listed in the Pandora Papers, sustained the colonial policies of land grabbing in Laikipia through private wildlife ranches and conservancies. The disenfranchised Maasai pastoralists are struggling against such oligarchies in what Kirir Sing’oei has dubbed Decolonize Laikipia.

The White Maasai

The Maasai (both real and fake) are also to be found at the margins of the extravagant tourism industry. Here is where the Maasai identity is commercialized at the industrial scale. Tanzania and Kenya are the world-class tourist destination marketed for their breath-taking natural and cultural beauty. The Maasai Mara (Kenya) and the Ngorongoro World Heritage Site and Man Biosphere (Tanzania) represent that combination of natural and cultural beauty. Besides the Big Five, the Maasai are a highly coveted sight among safari tourists.

Anyone that grew up in the same environment as mine must be aware of the curious smiling backpackers who politely invade your home (Boma) with laborious cameras. We also met them in Oserok (wilderness) while tending flocks and wondered about the motivations of their travel, their interest in us, and the wilderness. We even asked ourselves who was tending their cattle while they are wondering in the wilderness like wild animals.

What about their families? We called them Irkiriko (aimless nomads). Equally, we thought what they thought about us. We could ask several questions in our limited understanding of the complex realities, but we neither spoke their language nor did they understand ours. They appeared nice, but we were always suspicious of their smiles and curiosity.

One thing we certainly knew is that camera-carrying backpackers are the driving force behind big-game hunting that depopulated wild animals in our village lands. Even today, piles of skulls of the thousands of wildebeests, elands, and zebras can be seen at the foot of En’doinyo Alailili hill. Animals became restless and we could see how fast they could run whenever they hear a vehicle’s sound.

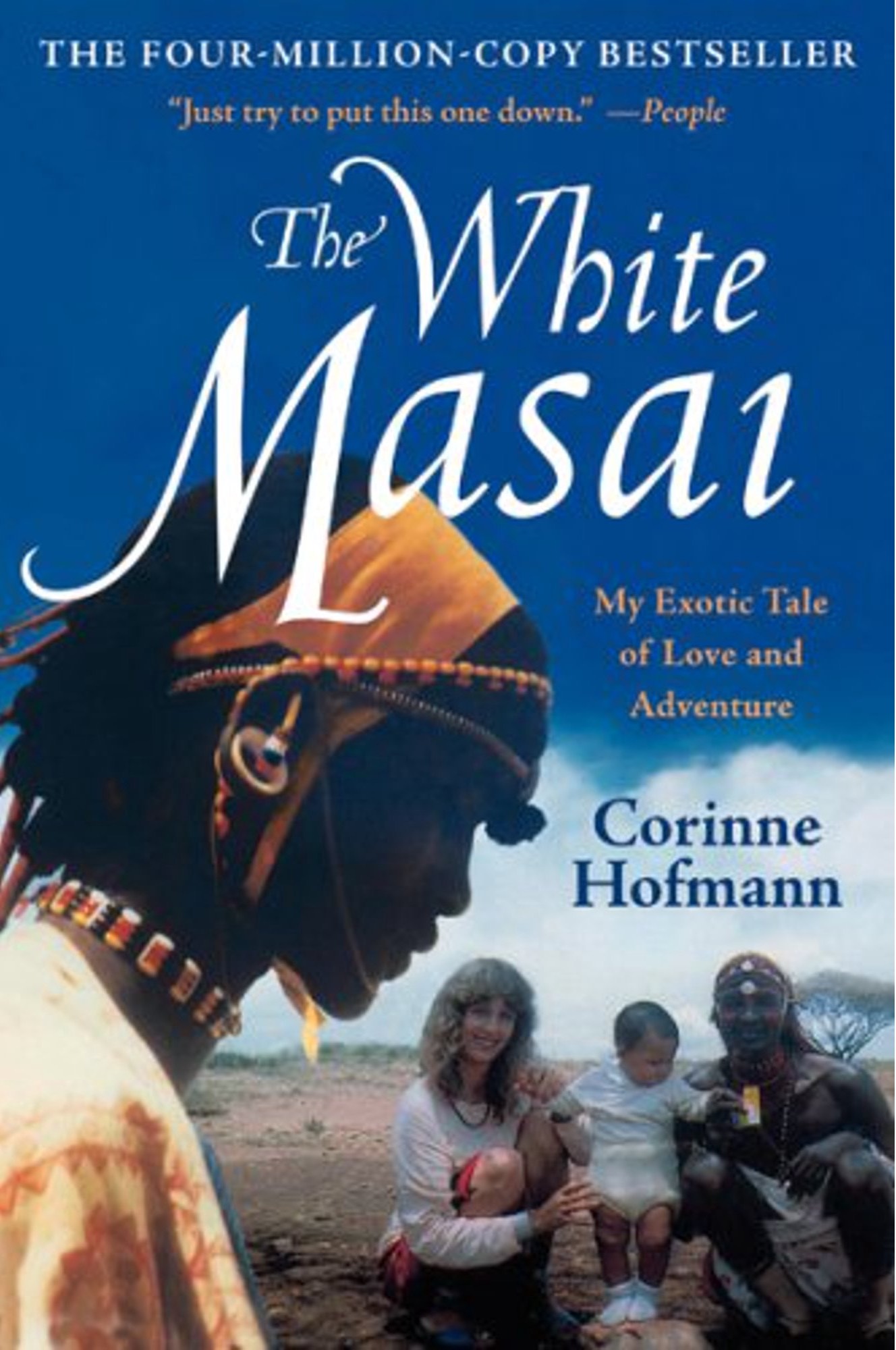

Luckily, I later found my way to school where I learnt reading and writing. Finally, I can read, write, and understand the backpackers’ language! When I started secondary school, I received The White Masai as my first or second gift book. I was intrigued by the title, but disappointed by the content of the story and the author’s tone.

A European entrepreneur, Corinne Hofmann, goes to Kenya as a tourist and meets Lketinga in a hotel in Mombasa where he performs traditional dances for tourists. She falls in love with him and give “up her Life” (mark the capital L) in Switzerland, a beautiful country in the heartland of Europe, for a Maasai warrior in the Kenyan bush! At the end she leaves him and go back to Europe with the daughter obtained from the marriage.

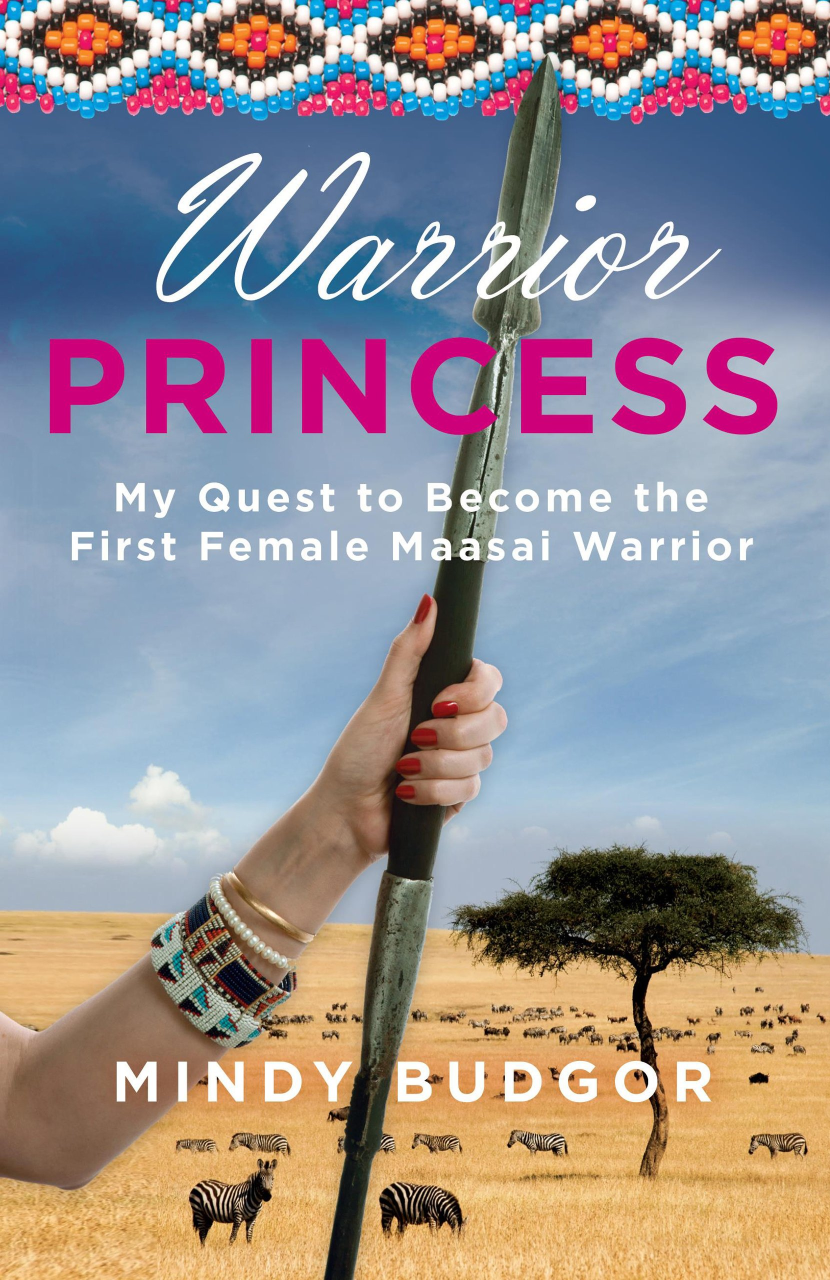

The book is a reflection of what is referred to by the British sociologist John Urry as the “tourist gaze”. This gaze is characterised by its nostalgic, romanticizing, patronizing, and colonialist overtones. Mindy Budgor is another white Maasai I have in mind. This one spent two weeks in Kenya and went back to New York already an expert of the Maasai culture, a “warrior princess” as she claims in her book Warrior Princess: My Quest to Become the First Female Maasai Warrior.

While I firmly believe in empowerment and the course of feminist struggles, I am cautious of NGoization of resistance which is so often detached from real struggles on the ground. I am against the Saviour-Savage dichotomy: presenting one individual or organization as a Messiah to the suffering “tribal people”. This perpetuates a paternalistic colonial mentality and downplays local agency, which is very critical.

A white lady (in Mindy) from the U.S. going to an African rural village to help the Maasai withstand lions seems fantastical enough. It is awkward. These self-proclaimed warriors use our culture to enrich themselves while insulting us at the same time. It took me 15 years to become a warrior, but it took Mindy only 15 days!

There is a lot of training and socialization one must undergo before arriving to warriorhood. It is earned after fulfilling the requirements of predetermined societal standards like obtaining substantial knowledge on livestock, local ecology, and learning to live a selfless life. All this is accompanied with rituals that serve as a sacred contract between an individual and the society as well as with the non-human world.

These folks come to our villages (as tourists, researchers, volunteers, or missionaries) expecting intimacy, and the innocent people who are ever welcoming, invite them into their homes. They share their stories, ideas, and lives with them. The Maasai or people from the Global South do not usually have such privileges.

Yet, due to white privilege, the Corinnes and Mindys of this world can go as far as appropriating even the sacred parts of our culture. They often do all this without consent, acknowledgment, or at least some sort of recognition – thanks to the absence of intellectual property rights in that part of the world. And they produce books and documentaries for the naïve audiences in the West that are desperate to experience the “wild, extraordinary primitive tribal people” whom the Maasai are assumed to represent. They then become bestselling authors and points of reference for understanding the ‘exotic’ Maasai.

Unfortunately, the whole idea of cultural tourism is predicated upon this gaze and some of us who have lived that reality know better the implications on the persons, animals or places that are gazed upon. For instance, in the cultural bomas, the Maasai culture is neatly packaged and presented to visitors to give them unforgettable memories about the land of Kilimanjaro and Zanzibar. This iconic culture on display showcases a legacy of European means of displaying ‘the Other’ shaped in the 19th century natural history museums, folk museums, and World Fairs.

At the Kilimanjaro International Airport (KIA), tourist hotels and campsites, white tourists are welcomed with a traditional Maasai dance. Here, the songs, the greetings, and hospitality are commoditized. This commoditized social reality is sustained through mystification and latent violence; hence, it becomes a false reality. Unpleasant facts, particularly those that have something to do with coloniality, internal othering, and the political economy of the tourism industry are usually erased from such simplistic artificial representations.

So, who accumulates? Who are the losers? Don’t tell me about the win-win nonsense because there are only winners and losers in colonial settings where local lives and livelihoods are destroyed while accrued benefits go to a select group of foreigners (captains of international tourism industry), corrupt national elites, and intermediary brokers.

It is estimated that as much as 70% of tourism profits in Africa are designated for foreign pockets. In Imposing Wilderness, Roderick Neumann draws parallels between the acts of enclosure (privatization and dispossession) via game laws, depriving local people of an important means of providing for their own survival. Creating tourism destinations frequently includes what Teresia Teaiwa calls Militourism – a phenomenon by which a military or paramilitary force ensures the running of a tourist industry, and that same tourism industry masks the military force behind it. In the case of my home country, Teklehaymanot G. Weldemichel aptly unpacks Othering Pastoralists, State Violence, and the Remaking of Boundaries in Tanzania’s Militarised Wildlife Conservation Sector.

While some Maasai pastoralists, out of necessity, have learnt to milk wildlife (incorporation into the tourism industry), many maintain a different attitude toward wildlife conservation and commercialization. They resent a world where nature is ‘protected’ within national parks and game reserves to be sold through tourism for profit to an elite few. This understanding of the world makes open resistance inevitable for ethical reasons. In the Maasai worldview, reciprocal human-nonhuman relations are fostered and respected and therefore no militarization, eviction, or displacement are tolerated.

In cultural tourism and ecotourism, the Maasai are pressured to commoditize their living culture and ultimately themselves. Dancing is a crucial performance in the Maa culture as it is in other cultures. The Maasai sing about the grasslands, the seasons, and the struggles associated with them, their beloved cattle, and the most compassionate black God (Engai).

In the tourist setting, these organic and spiritual elements of the peoples’ culture are appropriated and commercialized. Here, the Maasai dance with and for the foreign spectators in non-home places. One would wonder what the content of such songs is! Praising the cattle and the plains or guests and the mighty dollar?

What is clear is that the tourism industry is governed by Western tropes of representation drawn from popular images of ‘the Other’ (read the Maasai) usually cast from colonialist and orientalist gaze, exoticizing and reproduced through the consumer driven media. Poverty, lack of education, and limited options for meaningful employment often keeps many Maasai in unfair conditions at best, in cruel or inhuman ones at worst.

Well-known for their courage and loyalty, hotel owners recruit the Maasai youth to protect visitors from locals who seek to rob and or steal from them. Of course, they simultaneously serve as a tourist attraction to visitors. Yet they are not necessarily compensated for this.

Strangers in their own Land

Maasai pastoralists have always felt like strangers in their own land ever since the advent of formal colonialism in the 19th century. Cultural revitalization and organization have been fundamental for the Maasai people to challenge the system of endless accumulation by dispossession and displacement. They aim to recover or preserve their ancestral lands amid many historical traumas, socio-economic crises, and violence.

A quick look at the colonial library would reveal multiple forms of dispossession, alienation, and marginalization that have been visited upon the Maasai pastoralists. The British colonists viewed the Maasai as “backward wanderers” that had to be “settled” and “civilized.” The civilizing mission ended up depriving the Maasai of about 60% of their ancestral lands in and around the Great Rift Valley (in present-day Kenya and Tanzania).

In a recent TV show, Khalid Gangana, made the following rather shocking remarks,“you also eat rice, the Maasai eat rice nowadays; you the Maasai have become human being nowadays.” What people eat or not now have to do with their humanity? Surprisingly these remarks were made in a national television (Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation-TBC). Of course, one may say this was a joke, but I don’t think so. Even if it was, what message do we get from such a crude joke?

It is paradoxical that in a country praised for ethnic cohesion, it is not uncommon to learn about internal othering of indigenous groups leading traditional lifestyles. The Maasai are often referred to as Maliasili (Natural treasure or resource). Yet, sometimes they are even denied access to restaurants and bars in bigger cities like Dar es Salaam.

I am not saying that this is the only reality. There are some successes and I am proud of the Tanzania that the founding fathers envisioned that grew to be a nation envied by others. Yet, the disturbing truths I am telling here serve as a reminder that some more work need to be done to accept and embrace different worlding or belonging differently. There are different ways of understanding the world and therefore different ways of being in the world. Accepting and respecting them is the true art of inclusivity and sustainability. Instead of imposing a single scientific vision of understanding the world, we ought to embrace our diverse worldviews.

The Politics of Belonging

When President Samia Suluhu Hassan assumed the reins of power in March 2021, she immediately sounded the alarm that the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) is on the brink of vanishing, reiterating the old distinction narrative that pastoralists degrade the environment with their traditional nature-extraction practices. She ordered the responsible authorities to see how they can relocate some of the pastoralists to other areas, insisting that Tanzania has only two choices: to limit human population and save NCA or allow human activities and say goodbye to conservation.

On April 12th, 2021, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA) issued a 30 days’ notice with Ref. No. BF. 151/662/01/45, indicating a list of people supposed to vacate the area and delineating demolition of residential houses, schools, dispensaries, and churches said to have been built without permission from the authorities. The eviction notice prompted a strong opposition from pastoralists and land rights activists and made the government reconsider its decision. Edward Maura, a chairman for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area residents, opined with eloquence that:

…we as residents have a few things to say. First, we have heard our beloved, Her Excellency Madam President about the current status of the Ngorongoro Multiple Land-use Area… Second, we want to tell the Minister and the Government of our Republic that they are dealing with citizens who are guilty of no crime. We left the Serengeti-Moru, in 1959 following the agreement our forefathers made [with the British colonial government]. They agreed that the Serengeti be set aside as a national park while Ngorongoro was designed to be a multiple land-use model. We left our territories in the Serengeti and moved to Ngorongoro highlands. If it has reached a time that there is a need to renegotiate [terms of coexistence in the area], then know that you are dealing with citizens who have not committed any crime. We came here neither accidentally nor aimlessly. If there is a need for a discussion then we don’t need to just be informed, we want to be engaged: let us have a talk. And the discussion must be free because we have committed no crime!

Maura sums up the terrain of pastoralist politics of belonging from historical, social, economic, ecological, and political contexts. That conservation has a history, and it must be considered. That the Maasai are legitimate citizens, but often othered and/or foreignized to invisibilize their demands.

They are significant knowers, but often ignored by planners and conservators. They are not objects to be gazed upon, but a people struggling to have ends met and preserve their cultural values for a meaningful living. This is a call for a meaningful and respectful engagement.

With the ongoing crisis of the capitalocene, the pastoral economy is increasingly becoming unviable. With no viable alternatives, pastoralists who have not adopted other lifestyles end up living in precarious conditions at the margins of the modern economy. The once nomads of the plains, the Maasai are gradually becoming urban nomads, acting as moving stores selling cheap sandals and souvenirs.

The 1980s and 1990s saw an increasing migration of the Maasai youth to major cities like Arusha, Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, and Mombasa mainly as security guards. Decades of neo-liberalization and fortress conservation have impoverished the Maasai pastoralists, alienated, and polluted their lands. They have been forced to leave their homes in search of precarious work in urban areas because it is no longer viable for them to make a living locally.

As Kenyan-born Somali poet Warsan Shire writes in her poem, “Home”, “no one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.” The modernist and neoliberal policies in rural Tanzania have produced marginality and dislocation. They are continuing to threaten the sustainability of local modes of subsistence, which the Maasai culture is rooted in.

Celebrities, whether musicians, athletes, fashion designers, tourists, or researchers, who are impressed by elements of our culture and lifestyles, yet appropriate it in one way or another, must heed the Swahili saying, “ukipenda boga, penda na ua lake” (if you love a pumpkin, also love its flower). That is to say that they have a moral duty to be a voice against injustices visited upon the Maasai people. This is not meant to be performed out of pity or philanthropy, as many do, but as an ethical urge to undo the enduring colonial quest to appropriate, grab, and dislocate.

As we say in Swahili, nchi hii ni yetu sote (this country belongs to all of us).

This is a wonderful piece of work I ever read, it tells all about our culture commoditization of the so called TOURIST STAKEHOLDERS and the fake Masai whose trying to markets themselves on our backside.

I have nothing to tell you The upcoming PROFESSOR LEIYO SINGO. then hugs and handshakes of Congratulations.