Why Arusha and Kilimanjaro let alone Dar

es Salaam?

Chambi Chachage

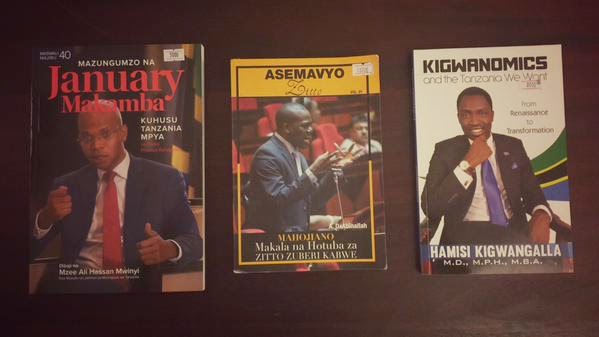

Regional development continues to preoccupy the new

breed of Tanzanian politicians. It appears in a

recent book on January Makamba’s answers. A

new book on Zitto Kabwe’s key speeches/articles and his online

debates addresses it. So does Hamisi Kigwangalla’s new

book.

What I find perplexing is the ongoing politicization

of statistics. It is one thing to present statistics on unequal regional

development and quite another to politicize them. The latter is so problematic

in the context of Regionalism

and Factionalism in Multiparty Politics.

The recently launched Tanzania Human

Development Report 2014 has come up with statistics that are prone to

such politicization. Before we delve into what politicians and their supporters

and detractors are saying let us dwell on what the report says. We focus on two

regions – Arusha and Kilimanjaro – that are hotly

debated in the social media.

After introducing UNDP’s Human Development Index

(HDI), the report (THDR2014) states: “While most regions in Tanzania have HDI scores

comparable to countries with low HDI scores, three regions – Arusha,

Kilimanjaro, and Dar es Salaam – have HDI scores comparable to those countries

with medium HDI levels.” Mind you, Tanzania ranks 159 out of

187 countries hence classified as low human development country.

In other words, these three regions are Tanzania’s

‘outliers’ – they are ‘way beyond the national average’ as if they don’t belong

to the country. The report even refers to them as the “most prosperous” and

among the “five wealthiest” regions in Tanzania. On a general level i.e. what

statisticians may say ‘on average’, the level of human development of the people

living there is more or less as that of the people in Malaysia and Mauritius.

Being the melting pot of Tanzania’s ethnic groups from

all 30 regions, Dar es Salaam is often let off the hook. It is Arusha and

Kilimanjaro that are left in the hot seat. Why?

Numbers ‘don’t lie’, do they? The bone of contention

comes from these figures in the THDR2014: Arusha and Kilimanjaro’s regional shares

of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is 4.77% and 4.54% yet their HDI ranks are

number 1 and 2, respectively. Note that the report defines the regional share

of GDP as the “percentage contribution of a region to the total GDP (national

GDP).” But it is also important to note that Arusha’s regional share of total

tax is 4.33%, second to Dar es Salaam with its enormous 81.4%.

Economist-cum-Politician Zitto underscores

that Arusha and Kilimanjaro are number 7 and 9, respectively, in their

contribution to the national GDP even though they are among the three regions

with more development. When queried about the regional shares of total tax,

which THDR2014 defines as the “percentage contribution of a region to the total

tax collected in the country”, he clarified that it is different from the regional

share of GDP thus sustaining his query on why, relatively, Kilimanjaro contributes very

little to Tanzania’s GDP while it is ranked number 2 in terms of the human

development index of the people residing there.

Honest as all this might truly be, such queries, when

not coupled with sustained historical and political analyses, are a fodder for ‘regionalism’

and ‘tribalism’. This is especially the case when they are uttered hastily and/or

carelessly in political podiums and parochial platforms. It is also the case

when they are reported – in colorful documents – out of their (historical) contexts.

For sure, and to his credit, Zitto has at least attempted

to analyze why the numbers are the way they are, albeit cursorily, on his

facebook. But a close examination of the debate in the social media, such as

the one going on in the exclusive

arena for Jamii Forum’s Great Thinkers, indicates that any lack of critical,

in-depth analysis only adds to the confusion that can easily ferment

parochialism especially when such a politician is on the record for publicizing

a particular region and feeding the discourse of belonging to a certain region.

Zitto’s mentor, Seithy Chachage wrote a Masters’ dissertation

on ‘The Development of Urban Capitalism

in Tanzania (With an Example of Arusha Town)’ way back in 1983. This is

what he had to say: “From the research, it was evident that the development of

Arusha town is not simply a regional phenomenon, in the sense that it has been

developed by the indigenous people of Arusha region; but part of a national

phenomenon.”

Chachage thus continued his presentation: “This fact

is clearly discernible from the nationality composition of the town

population, whereby there is a numerical dominance of people from Kilimanjaro

and the Central Tanzania regions.” These and other findings of his that are

revisited herein are useful in the sense that they help us to understand the (historical)

antecedents to what we are observing today when we look at all the dazzling THDR2014

statistics of how Arusha and Kilimanjaro are among the ‘big five’ in adult

literacy, pass rates in primary education, income tax and the Gender

Development Index (GDI).

Of course Chachage was focusing on Arusha town and

Manyara region had not yet been formed. By 1998 the patterns in his observation

had hardly changed as this

profile from the Planning Commission and the Regional Commissioner’s Office

indicates: “Arusha region shows a very high net inward movement of people of

141,724 second to that of Dar-es- Salaam region of 500,621 net migration. Such

direction of movement indicates movement of people in search of new farming areas

or employed jobs. Arusha town due to its large number of manufacturing

establishments has tended to attract many people.”

My professor of Economics, Nathan Nunn, cautioned me

about the importance of dividing any development index with its respective ‘historical

population’ when I was so excited about comparing the role of the variation of regional

development in reproducing elites in Tanzania. I think the population is one of

the keys to understanding the comparative economic history of Arusha and Kilimanjaro and

why the people there may not appear as contributing much to the national GDP

relative to what they have and in comparison to other regions.

GDP “per Capita” is aptly defined in THDR2014 as “GDP

divided by population” and it “represents the average resources available to

each individual in the population.” In the case of Arusha, ranked number 3, it is

Tsh 1,258,334. For Kilimanjaro, ranked number 5, it is Tsh 1,237,761. If read

differently, it is the ‘economically active’ (aged somewhere between 14 and 65) among 1.69 million people

in Arusha and 1.64 million people in Kilimanjaro who contributed to these GDP in their respective

regions. In both cases, they are nearly half since they constitute about 55.1%, according to the report.

Doing such a reading enables one to see that the contribution of

regional GDP to the national GDP is not simply about what region own natural

resources such as mining and touring sites. In the disturbing case of a ‘poor’ country

such as Tanzania that is not benefitting radically from its rich resources, the

‘wealth of the nation’ ought to be a ‘critical mass’ of the relatively healthy and well educated. Perhaps it is better to be happy about the apparent prosperity, that is, if it

is indeed not exploitative and if it is surely releasing the ‘prosperous’ from being a ‘burden to the nation’ thus propelling development in other regions through a

‘trickle down effect’ as they move to, or work in, the relatively less wealthy areas.

Kilimanjaro and Arusha have been pulling ahead since

colonial times not least due to many factors hence what we have been witnessing

since 2001 in terms of the decline

in their contribution to the national GDP is more about the decline in the

sectors associated with natural resources that is not necessarily affecting negatively

the strides and gains in the said prosperity/wealth that their dwellers (and

descendants) have accumulated across time. It is also about some regions ‘catching

up’ and our commercial capital outdoing its ‘colonial heydays’ when Hamza Mwapachu

thus aptly complained in 1950: “Up to now it is everything in Dar es Salaam to the

neglect and expense to the other centers in the territory.”

Visiting our country on the eve of independence,

Kathleen Stahl had this to say in 1961 about the then Northern Province’s ‘heart’ of Kilimanjaro in her colonial(ist) memoir on Tanganyika:

Sail in the Wilderness: “Chaggaland is a yardstick for other parts of

Tanganyika. It represents the highest standard reached in economic prosperity,

in local government, in social development.”

John Iliffe could not agree more in 1979 when he thus

stated in his magnum opus on A

Modern History of Tanganyika: “Regional disparity remained much more striking

than social differentiation…Dr. von Clemm’s study of the Lyamungo area in

Kilimanjaro in 1960-1 provides an illustration…Three homesteads in five had

concrete houses…One object of competition was education, valued almost entirely

in terms of money and power…Branches of the major banks existed on the

mountainside…Western medicine was highly valued…Kilimanjaro was at one end of

the spectrum of Tanganyika’s societies. Close to the other end was Buha [i.e. Kigoma]…[it]

remained a labour reservoir…”

Understandably, Chachage thus followed suit in the 1983

dissertation cited above: “In essence, Moshi town [in Kilimanjaro region] was

by 1960 much more developed commercially and industrially than Arusha town…The

general expectation towards the end of the colonial period was that Moshi town

would develop faster than Arusha town.”

Lest we forget, Chachage also made this poignant observation

in regard to Arusha town ‘overtaking’ Moshi town: “In-migration in Arusha

constituted little more than 1% per year to urban growth during the colonial

period. However, from 1957 to 1967 rural-urban migration played a significant

role in urbanisation…. While during colonial period it was the Wairangi and

other nationalities from the central regions who constituted the biggest percentage,

after independence the trend changed to the extent that Wachagga constitute the

biggest single nationality in town.” That was back in the days when our National Census had ethnicity as a

component.

Questioning tribalism and racism by way of disclaimer

in his dissertation, Chachage nevertheless thus continues with the analysis of those ‘regional dynamics’: “The dominance of the people from Kilimanjaro in Arusha

town is an expression of the fact that with the removal of the fetter imposed

by colonialism, both capitalists and the landless peasants who had emerged in

the more capitalistically developed areas such as Kilimanjaro were able to move

to urban areas. In Kilimanjaro, the capitalists sought to expand their

enterprises, which were constrained by the limitations in land ownership in the

areas and the landless moved to the urban areas to seek for wage employment.

Arusha town, more than Moshi offered the possibility of expansion because most

land was owned by foreigners who were already moving out, as opposed to Moshi;

whereby the expansion of the town itself entailed some form of land alienation

due to the population pressure.”

Yet, now in 2015, Zitto is telling us that Kilimanjaro, and particularly Moshi, is being exploited by Arusha especially in tourism. But it is our failure – as a nation, not a region – to capitalize on this sector and related ones during our ‘divorce’ with nationalization and ‘honeymoon’ with privatization that partly explains why Arusha’s contribution to the national GDP does not reflect the prosperity of its people as captured in its regional GDP. In 2005 Chachage and Usu Mallya made the following apt observation in their paper on ‘Tourism and Development in Tanzania: Myths and Realities’ that portrays this demise:

“The set up and the links that exist between ‘local’ tour operators and foreign ones; and the fact that vertical integration in the industry, to the extent that even Euro Car and other European ground transport companies are well established in the country, makes one conclude that between 75 and 90 percent of money paid for a holiday in Tanzania is either paid in the country of origin of the tourists or leaks out of the country. The major hotels, that have their own ground transport to cater for their clients, work to marginalize the local transport and tour operators. Moreover, as much as 50 to 70 percent of the earnings from hotels and tourism in general go to acquiring imports of goods that the sector demands—mostly exotic imports. The dominant position of the foreign operators means that profits are ploughed back home, leaving very little revenue in the destination country. Package tourism is quite notorious for funneling away tourism revenues… tourists pay for the whole vacation in their home countries bringing only pocket money to buy souvenirs and incidentals…. The country is not only losing money in terms of foreign exchange and leakages, but also in terms the amounts of money it has been compelled to use from taxes and loans for privatization of facilities, sustenance of incentives for investors and creation of infrastructure to service tourism….”

Probably they were anticipating this pertinent

observation that the

journalist Annastazia Freddy made in 2013 when another report came up

with statistics on which region contributes more to the national GDP: “One of

the reasons for the low rank of Arusha in the economy of the country could be

because most tour companies are foreign or Dar es Salaam-based, which means

that most of the money tourists pay for accommodation and travel remains

outside Arusha. “Many tour companies are foreign-owned. In fact this also raises

the question of how the country benefits from the tourist attractions found in

the country if most of the money paid remains outside the country,” a worker at

a Dar es Salam-based travel agency, who requested for anonymity, told The

Citizen yesterday.”

Statistics are not simply collections of facts. They

are both objective and subjective. No wonder Chachage wrote a critique on ‘using

statistics to trick the masses’ that appears in his recently

published eponymous book. We should all be wary of the politics of (regional)

numbers.

Xenophobia is fanning regionalism in Africa. Yes, let us

restructure/transform our economy. Carefully.

Am from Arusha so you will forgive my bias if pronounced by mean. My observation is that the analysis of those region separately will be hard- from endogeneity issues to measurement issues.

Ok endogeneity- how do you separate moshi and arusha people who works in Dar and Identify both cities as home? . How do you separate their income? My understand is that we don’t declare taxes according to cities you live?

On HDI I suppose network effects tend to reinforce the colonial foundation of education in the region and hence the mushrooming of all this schools in the region. Just as wealth beget wealth so does education and any other institutions initiated in a region tend to benefit from network effect as well.

On tax contribution- my understanding also is that tax does not gauge the HDI or economic growth and at time is actually purely independent of GDP, e.g if say majority of People of area A engage in certain activities with have leaner tax compare to others- despite how productive they are, it won’t reflect in taxes.

Lastly the type of activities , the cities network and HDI actually explain the phenomenon you explain here perfectly for Arusha and Kilimanjaro- there is no paradox in data!

Yet remember the caveat am from Arusha and I could also be wrong.