In these times of historical amnesia and selective memory, the passing of Frene Ginwala may largely go unnoticed in Tanzania. This may not come as a surprise generally in a country that hardly pays close attention to its sites of memory—historical landmarks of the liberation struggle in Southern Africa across Dar es Salaam. From a house at Yasser Arafat Road that harbored hero-turned-villain Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe to the one with a plaque in Msasani Road where the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique’s (FRELIMO) leader, Eduardo Mondlane was assassinated.

This is a rich history—or herstory for that matter—that Frene belongs to. As my colleague Shireen Hassim has put it, Frene facilitated movement of members of the liberation struggle in South Africa into exile through Mozambique and Zimbabwe. She also became an exile in Tanzania. Her role there included setting up the office of the African National Congress (ANC).

Frene was many things to Tanzania and one of its predecessors—Tanganyika. My interest here is not to recount her turbulent relationship with the Tanganyikan/Tanzanian state. Shireen has summed that up well in her tribute. It is indeed Frene’s “independent and forthright views” that led President Nyerere to ban her. Yet, I may add, it is the same independence and forthrightness that led Nyerere to ask Frene to return and become the managing editor of a nationalized newspaper.

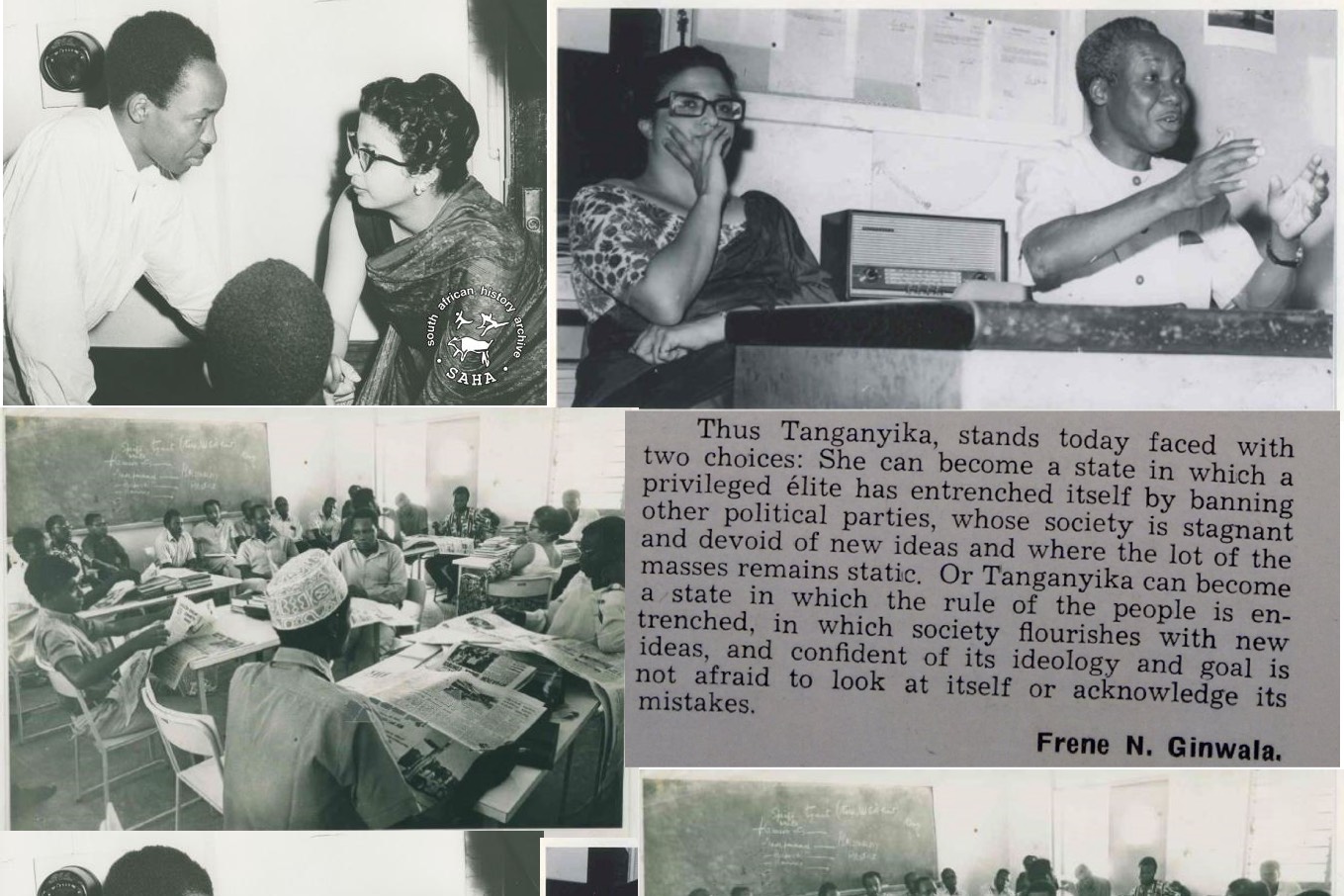

One gets a glimpse of this consistency in her scathing critique of Nyerere’s move to abolish multipartyism in the 1960s. Frene singlehandedly questioned the president and his right-hand man through what she rhetorically entitled ‘No Party State?’ She then prophetically concluded:

Thus Tanganyika, stands today faced with two choices: She can become a state in which privileged élite has entrenched itself by banning other political parties, whose society is stagnant and devoid of new ideas and where the lot of the masses remains static. Or Tanganyika can become a state in which the rule of the people is entrenched, in which society flourishes with new ideas, and confident of its ideology and goal is not afraid to look at itself or acknowledge its mistakes (Spearhead Vol II. No. 2: February, 1963, page 3).

She lost the battle. But not the war. Many years later in their lifetime it was Nyerere himself who partly spearheaded Tanzania’s return to multipartyism. It was quite a sight and reencounter when Nyerere addressed the first post-apartheid South African parliament. Flanked by its Madam Speaker, none other than Frene. One can only imagine what went in their minds and eyes when—and if—for a moment they reflected on the fact that it was a multiparty parliament.

Another battle that she spearheaded in the 1960s is that of freedom of the (public) press in Tanzania. This was tricky given the turn to single-party statism. Frene ensured the nationalized paper that Nyerere had asked her to be its managing editor had this public president’s charter.

The new Standard will give general support to the policies of the Tanzanian Government but will be free to join in the debate for and against any particular proposals put forward for the consideration of the people, whether by the Government, by TANU [Tanganyika African National Union], or by other bodies. Further, it will be free to initiate discussions on any subject relevant to the development of a socialist and democratic society in Tanzania. It will be guided by the principle that free debate is an essential element of true socialism, and it will strive to encourage and maintain a high standard of socialist discussion. The new Standard will be free to criticise any particular acts of individual TANU or Government leaders, and to publicise any failures in the community, by whomever they are committed. It will be free to criticise the implementation of agreed policies, either on its own initiative or following upon complaints or suggestions from its readers (Tanzania Standard, February 5, 1970, page 1).

What added more weight to the charter is that Frene ‘convinced’ Nyerere to state this publicly:

The new Standard will aim at supplying its readers with all domestic and world news as quickly as possible. It will be run on the principle that a newspaper only keeps the trust of its readers and only deserves their trust if it reports the truth to the best of its ability and without distortion, whether the truth be pleasant or unpleasant (Tanzania Standard, February 5, 1970, page 1).

During her tenure, Frene arguably adhered to the principle of this charter to the best of her ability. In that sense one can confidently say she won the battle, but partly lost the war in the long run as national media became more of government/state media after she was forced to leave again. What is crucial is that she contributed to preparing the battleground for what has continued to rage on across varying post-Nyerere regimes. A quest to make the Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation (TBC) and Tanzania Standard Newspapers (TNS) truly public. By, with, and for the people.

Kwaheri Frene, Buriani Ginwala, as we say in Kiswahili. You taught as well. Hamba Kahle.

marvelous treatment of part of her history. The problem here is purely technical: poor choice of text and background colours, leading to bad readability due to contrast problem. Please rectify this technical error. You would have scored better had you done that.

no further comment.